Building a Project Budget

Creating a good budget does not have anything to do with liking math or being a numbers person. It is a form of storytelling.

Just like a 60-second elevator pitch or a 500-word narrative, a project budget is a tool for communication. It is an incredibly useful tool for helping individual artists conduct their practices within financial limits. Project budgets are also a way to share information with a grant review panel, potential donors, and other team members. Creating a strong project budget simply requires artists to present the hard work they are already doing in a new format.

What is a Project Budget?

A project budget is a specific amount of money allocated for a particular purpose over a specific period of time. Project budgets are different from operational budgets, which track the annual income and expenses of an entire organization. Examples of projects include curating an exhibition, directing a short film, or creating a site-specific piece of theatre.

Revise Revise Revise

Since the needs of all projects change over time, revision is an essential component of budgeting. Artists are already pros at making changes to their creative work. This same skillset can be applied to budgeting. By drafting a budget early in a project’s planning process and then periodically assessing and adjusting the budget in accordance with new expenses and funding opportunities, the budget evolves alongside the project. Having an up-to-date project budget on hand makes it easy to share at a meeting or supply one for a last minute deadline.

Step-by-Step Tips for Project Budget Building

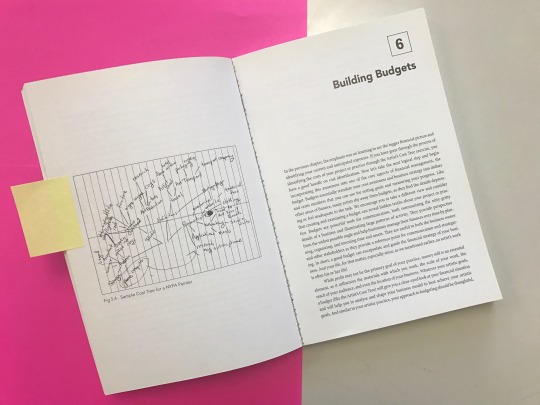

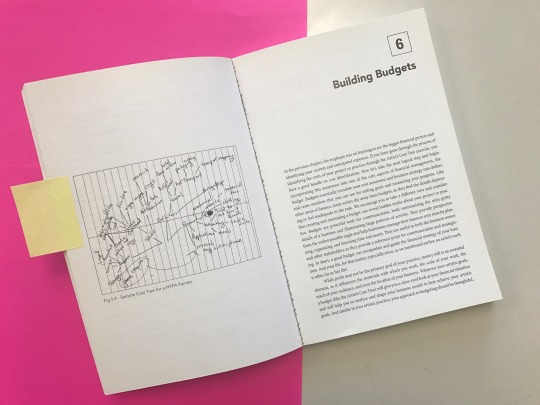

1. Brainstorm Expenses: Begin by considering everything about the project that costs money. Nothing is too small to skip. An artist ‘cost tree’ is a brainstorming tool to help artists gain a comprehensive understanding of expenses associated with their project. Some things to keep in mind:

- What are the main expenses?

- What specific costs are associated with these primary expenses?

- What are are smaller expenses associated with each sub-category?

- Remember to pay yourself a stipend or hourly wage! To determine your hourly rate as an artist, check out the formula at the end of this post from Andrew Simonet’s book Making Your Life As An Artist. Simonet is the director and founder of Artists U.

2. Organize Expenses: Group similar types of expenses together to create line items on your budget. For example, plaster, burlap, and buckets could be grouped under a ‘Materials’ category. Depending on your budget template, all of the details and subcategories you captured through brainstorming can be listed in a corresponding ‘Notes’ section, or broken down into separate line items.

3. Assess Sources of Income: Income for a project can be categorized into earned income, unearned income, and in-kind support.

- Earned Income – Wages, tips, and salaries you receive from employment. Sales from works of art or tickets to an event are also examples.

- Unearned or Contributed Income – Sources other than employment and profit from a business, such as interest from savings and stock dividends. For artists, unearned income can also come in the form of project grants, fellowships, cash prizes, and gifts.

- In-Kind Support – Goods and services that are not monetary, such as living accommodations during artist residencies or donations of materials.

4. Assess Status of Income: It is important to note in your budget if income for the project is committed or pending. For example, if you already received a grant for a community engagement project, these funds are committed. If you applied for a cash prize but have not received it, this money is pending. It is appropriate to include and designate which funds are committed and pending.

5. Estimate with Care: Budgeting requires that you make estimates of projected income and expenses. To accurately do so, rely on resources such as past experience, experts in the field, and publicly available information. Be as specific as possible, never underestimate the power of common sense, and remember to make conservative estimates. As The Profitable Artist suggests:

Do not underestimate the value of your peers’ advice. All artists have to deal with finances, and it might help to ask a few trusted friends to compare notes on expenses, pricing services, etc.

6. Put It Together: Generally, when submitting a project proposal, the expense and income sides of the budget should balance to zero. If you are applying for a grant, always use the budget format requested by the funder. If you are keeping a budget for your personal records, find a strategy that works well for you. Use a spreadsheet in Excel or Google Sheets to organize information and build formulas within the document. Check out these sample project budgets from the Foundation Center’s Grantspace website.

Your Project Budget

Budgets are adaptive to the creative process and are another method for translating an artist’s idea to funders and project team members. They are excellent tools for conveying objectives, and providing frameworks and timelines for reaching project goals to an audience. When a project is complete, its budget remains a helpful guide for measuring outcomes, evaluating progress, and defining its success.

Looking for more resources? NYFA’s The Profitable Artist is a resource and comprehensive career guide for artists of all disciplines.

Excerpt on Determining an Artist Fee, from Making Your Life as an Artist:

Artists don’t know what our time costs. People ask us to do residencies, workshops, artist talks, etc., and to make our lives sustainable, we need to know our rates.

Take the annual income number you just figured out and divide it by 1,500 to get your hourly rate.

Why 1,500? If you work a “normal” job for a year, you’ll work 2,000 hours (40 hours per week for 50 weeks) Artists don’t have 2,000 hours to earn our living. A lot of our work is piecemeal, a teaching gig here and a day job there, with lots of prep, travel and transition time. And we need more down time than most people to feed our imagination and vision. Artists who earn their living in 1,500 hours find sustainability.

Once you have your hourly rate, multiply it by 8 to get your day rate (8 hours in a work day), and multiply your day rate by 5 to get your week rate.

Here’s an example. Suppose you decide you need to earn $45,000 per year to live without financial panic.

45,000 ÷ 1,500 = $30/hour

30 x 8 = $240/day

240 x 5 = $1200/week

Interested in fundraising through NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship for your next great idea? Our next no-fee application is due June 30, 2017. Learn about our Fiscal Sponsorship program by clicking here.

– Madeleine Cutrona, Program Officer, Fiscal Sponsorship

Images, from top: courtesy of Writing On It All, a fiscally sponsored project by Alexandra Chasin; a cost tree in The Profitable Artist, photo by Amy Aronoff