EXPLORING SCULPTURE WITH BUNDITH PHUNSOMBATLERT

“For me, functionality is very connected to the design aesthetic and cannot be separated from the conditions of living and social context.”

Artist Bundith Phunsombatlert works at the cross-roads of traditional and new media, thoughtfully traversing boundaries of installation and sculpture, while living between New York City and Bangkok, Thailand. His site-specific project Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures creates opportunities for the public to engage on self-guided tours of New York City’s diverse public sculpture and is fiscally sponsored by NYFA. Phunsombatlert generously shares his insights about Wayfinding, art making philosophy and reflections as an immigrant artist.

NYFA: Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures is composed of one hundred directional signs that mimic US National Park signage. Each sign includes a drawing of a public sculpture in NYC and the distance, mapped with GPS coordinates, between the sites. In addition to the clairvoyant graphics, the project’s online map empowers viewers to journey through NYC and experience public sculpture. Such considerations allow participants to easily traverse the city and demonstrate your commitment to accessibility. What fuels your inspiration for Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures?

Bundith Phunsombatlert (BP): Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures is mainly inspired by my personal journey and the basic question of what art means to people, including myself as an artist. I first came and stayed in NYC in 2007. In the beginning, the way I could remember places was not from the names of the streets, but visually through the permanent public sculptures in each area. There are a lot of public sculptures in NYC, more than any other place I have been to. This work has the idea of remembering places through the experience of my own journey.

Then I started to map these public sculptures. The process for making this project is to research all existing public sculptures in NYC and identify 100 sites to be incorporated in my final work. I went to visit each location to photograph all of the sculptures and record the GPS coordinates. Afterward, I created a small drawing for each sculpture and developed directional signs. An online map was created for people to find where each sculpture is located, as well as the artist names, years, and the title of the artworks.

For me, this project is not only a collection of directional signs, but it is public art by itself. This public art is a wayfinding for people to find other public artworks. The project contains different layers of thoughts. The first layer this work questions is, “Is the artwork an object?” Or, is the artwork all about the interpretation of the audience? How can the journey of people between the representative sign and original sculpture be an artwork in itself? Or, in this case, maybe the gap between the audience and the artwork is an important piece of art itself? This is rooted from my experiences working with interactive projects where the space of interactivity is not only for people to participate in, but it is also the message of the artwork itself.

NYFA: How do the disciplines of art and design each influence your creative practice?

BP: I have been exploring how functionality can play a role in my art practice from diverse forms of art, such as print media, multiple sculptures, interactive installation, etc., since the beginning of my career. For me, functionality is very connected to the design aesthetic and cannot be separated from the conditions of living and social context.

NYFA: Why is functionality important to you? How do you engage the audience in this project?

BP: Functionality is one the most important conceptual and aesthetic concentrations in my works. As a media artist with a background in printmaking, I work between old and new media. I studied both a BFA and MFA in printmaking at Silpakorn University, Thailand, and then a MFA in Digital+Media at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Wayfinding contains the interpretation of functionality on the visual art side as well as the use of functionality from the media art perspective. When people are at the installation site, without the need for travel or motion, they can imagine their journeys to find the sculptures they like, or think of their experiences of the sculptures they have already seen. The work engages the public to interpret the original public sculptures through their physical journeys, experiences, and memories.

Although Wayfinding is an interdisciplinary project, the work combines the practice of printmaking as an old media to one of technology as a new media. Audience agency, the use of GPS coordinates, a digital compass, and an online map, transform the definition of public art by introducing a more robust component of exploration and navigation. The work conceptually questions how new media creates new meaning from something through the process of reactivating the public artworks. Their [the sculptures’] established meanings will change as they are discussed by people face-to-face at the installation sites or online through social networks, bringing them to life in new media.

NYFA: Each sign in Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures contains an image of the sculpture it is referencing. Why did you draw these images, instead of using another method of documentation such as photography?

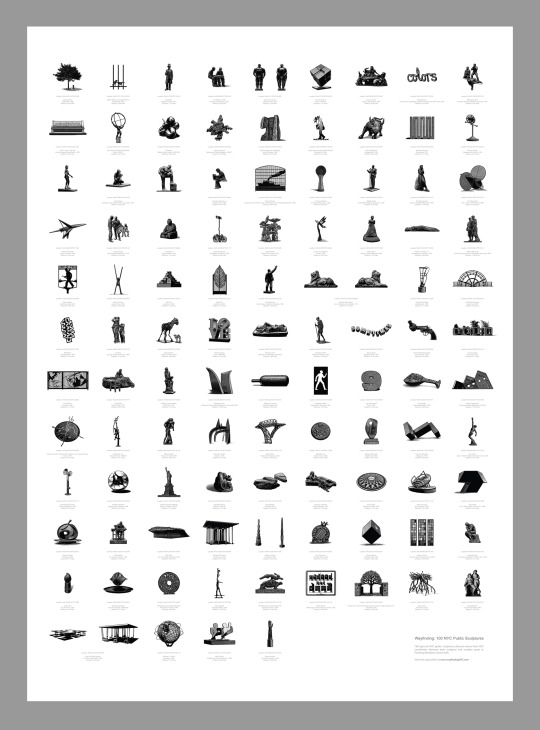

BP: I drew all of the one hundred public sculptures using a digital pen from the photos I took. They are all in black and white to play with the experiences of people and their memories. All drawings have their own details to make them different from one another. I did this because several of the sculptures are quite similar to one another in black and white, for example Isamu Noguchi’s Red Cube and Tony Rosenthal’s Alamo.

From my view, this project also incorporates the curatorial practice into the form of artworks. Through the process of selecting the sculptures, choosing the best angle for each sculpture, transforming them through drawings with the best representation of light and shadow, and then redistributing them back into the public space, this entire process is not an exhibition, and rather than being an exhibition of artworks, it is an artwork within itself. This quality is intended to blur the area of curatorial work and artistic practice.

NYFA: What criteria did you use to narrow all of the public sculptures in NYC to the one hundred sites incorporated into Wayfinding?

BP: To start, they need to be permanent public sculptures in NYC. The way I narrow down these sculptures to the one hundred sites is to have the diversity of public art from five boroughs of NYC. Then, I do research on all the existing public sculptures in NYC. Fifty percent of the artworks I have on the list are iconic and they are the landmarks that help locate people. Another 25 percent of the artworks are not very well known. And the last 25 percent are hidden public art pieces.

Also, when I went to visit each sculpture during my research, some of them were under construction and temporary removed from the sites. Some of them were installed at the sites with a lot of obstructions to see the overall sculptures. Because of these conditions, I could not include all of the interesting art pieces I found.

NYC has a large number of great public artworks. Wayfinding is not only a guide for people to find the permanent sculptures on the list, but also to think about the entire idea of public art in NYC. As Jennifer Lantzas, NYC Parks’ Public Art Coordinator stated, “Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures is an exciting and rare instance where our temporary public art program will merge with and inform the permanent sculptures in New York City’s collection.”

NYFA: Your artist statement notes that you view the world through the “framework of globalization.” Based on your experiences growing up in Thailand and later moving to the United States, how does your perspective as an immigrant artist influence Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures?

BP: I live and work between NYC and Bangkok. As an artist originally from Thailand who has worked in several countries and cultures, I think carefully about how my position changes as I move in and out of my homeland to another place. Carefully considering the history of a culture or a place, I analyze and synthesize these situations in order to develop artwork that reconsiders new identities in the globalized era.

I have been in and out of NYC for approximately eight years. As an artist I consider—how can I combine both the context of the place where I stay in and the experiences from the journey of my life? How can I balance myself in a new environment and define the relationship of the individual to others on a global scale? These questions reflect the experiences of transformation I have had as I moved from my country to the US. And, of course, the Wayfinding project also reflects these transformational experiences.

NYFA: In 2013 you received a NYFA Opportunity Grant for Wayfinding. The award, open to NYFA fiscally sponsored artists and organizations, is designed to further artists’ careers. How did you invest this award into your practice?

I received the NYFA Opportunity Grant in 2013, along with other financial support, which was used for the production of the Wayfinding project to be realized at Flushing Meadows Corona Park in 2014. This award is one of the first I received for this project, so it is very encouraging and allowed me to develop the work further.

NYFA: Our Doctor’s Hours is a program that allows artists to meet one-on-one with arts professionals and gain feedback about their work. As a participant of Doctor’s Hours, how have such interactions influenced your practice?

BP: For me, an opportunity for artists to meet one on one with various arts professionals is like a quick studio visit to get feedback and ask direct questions. This is similar to when artists are in the residency program where guest critics are invited to visit their studios. NYFA’s Doctor’s Hours program has a great variety of experts from different fields, such as curators, gallery owners, writers, financial and fundraising consultant, etc. This is one of the great ways to learn about the New York art scene and begin to connect with the community.

NYFA: What are the most challenging and exciting parts of creating art that requires human participation?

BP: For me, the most challenging and exciting parts of the project is when people first interact with the project. How do people enter the artwork? How can they find the project’s relation to themselves? And, then how does this relationship develop as a message?

NYFA: In what ways did you utilize NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship to help fund Wayfinding? Based on this experience, what suggestions can you offer to individual artists interested in working with art and technology?

BP: I have two projects fiscally sponsored by NYFA: Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures and T|r|a|n|s|t|r|a|c|k. Both are art and technology related projects, which are very expensive and time-consuming. For me, there needs to be a balance between the experience of using technology and fine art aesthetics to come together in one project. For specific or long-term projects that require significant financial support, NYFA’s Fiscal Sponsorship program enables artists to apply for the grant that they could not otherwise apply for as an individual. The staff and resources they provide are also very helpful and encouraging.

NYFA: What is the next iteration of Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures?

BP: Wayfinding: 100 NYC Public Sculptures developed at Socrates Sculpture Park and expanded with the support from New York City Parks & Recreation. The first location was at the lawn in between the Queens Museum and Unisphere at Flushing Meadows Corona Park, from May 14, 2014, until March 31, 2015. The second and final location will be in Manhattan (in progress of permission) and will be exhibited in 2015.

In order to fundraise for a new version of the online map, the production and installation for the final location of Wayfinding project I created 50” x 36” archival digital prints. They contain all my drawings of 100 selected NYC public sculptures with the distance from each GPS location (customized by the collectors’ request) and the original sculpture, as promotional material. Please visit www.wayfindingNYC.com to stay updated with the project!

Inspired to support public sculpture? You can make a tax-deductible donation to the next iteration of Wayfinding at Bundith Phunsombatlert’s NYFA Artist Directory page. You can also learn more about Wayfinding and interact with its website

To learn more about NYFA’s Fiscal Sponsorship program click here.

– Interview conducted by Madeleine Cutrona, Program Assistant, Fiscal Sponsorship

Images, from top: Photo Credit Bundith Phunsombatlert; Image Courtesy of Bundith Phunsombatlert; Photo Credit Bundith Phunsombatlert; Photo Credit Jan Mun