Meet a NYFA Artist: Dawn Clements

NYFA speaks with 2005 Fellow in Printmaking/Drawing/Artist Books Fellow Dawn Clements

NYFA: Hello Dawn, thank you for taking the time to share your current news and work with us. What are you working on right now? What has recently happened for you, and what are you looking forward to?

DC: I am currently living in the Los Angeles area, working as visiting faculty at CalArts for the Spring semester. In June I’ll be back in Brooklyn. I just finished a large ballpoint pen ink drawing that is being shown at Lesley Heller Workspace in New York, I’m showing work at the Boiler (Pierogi) in Brooklyn, the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock, and Voorkamer in Lier, Belgium. I am making drawings in California in response to my environment here. I’ve loved being in California. I am preparing new work for a 2013 exhibition with Francoise Petrovitch and Elly Strik at the Fondation Salomon in Alex France.

This past January at Pierogi I showed some new work created in collaboration with sculptor Marc Leuthold. It was wonderful to show this work that had been in progress for about 3 years. In that exhibition I also showed a drawing that I made in response to the work of dancer Susan Rethorst. I’ve also traveled quite a bit in the past year. Responding to new works, media and places has been very fruitful.

This past month I was selected as a Civitella Ranieri Fellow and a Guggenheim Fellow. These are tremendous honors for me and I feel very grateful.

NYFA: Where did you grow up and what was your childhood like? How did this influence your work, if at all?

DC: I grew up in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, a suburb of Lowell. My parents were great believers in a well-rounded education with a strong emphasis on art and music.

My mother was and is a caring and deeply loving mother. She made her living as a nurse, working the graveyard shift so she could take care of us during the day. She loved art and music. She used to make beautiful clothes for me and once she took a drawing course and made some very interesting work. She is very attentive to detail.

My father was an artist who worked in his studio every single day, but he never made his living as an artist. He had a full-time white collar day job that he really didn’t like. When he came home from work he’d go down to his studio in the cellar. I’d often sit on the cellar steps and watch him work. He taught me how to draw. There came a point when he decided to stop painting, but because he felt he might want to paint again some day he developed a habit of doing 10 drawings each day. For about 40 years he almost never missed a day. I’m not certain that he considered these drawings “art.” He did them to stay in practice in preparation for the day he decided to paint again. Each drawing was a simple line drawing of nude female figures based on life drawings and paintings he had done in the past. Over the years, he stopped referring to the source images and I suppose just responded to the previous drawing. Each drawing took less than a minute to do and was usually done in black ink on a piece of 8 ½ x 11 inch typing paper. Sometimes the medium was India ink and a crowquill pen, sometimes a ballpoint pen, sometimes Sumi ink and brush. Over the years these drawings were stacked in column-like piles in his studio. Eventually he took up painting again, but the habit of daily drawing continued until the day he died.

My parents got an used upright piano. Neither of them played, but they loved music, and thought it was important that my 3 younger brothers and I studied piano for at least a year or 2. If we didn’t like it, we could learn another instrument, but we had to study music. My mother and father just thought it was an important part of our education. I studied classical piano and thought I would be a pianist, but I really wasn’t so good at it. I worked hard at it, but I mustn’t have worked hard or well enough. I love music though. I love to play and sing and I love movement. I know this affected me deeply and contributed enormously to who I am as an artist. It affected my brothers too. Today they are all musicians, a pianist, a drummer and a saxophone player/ethnomusicologist.

We lived in a very small house filled with a lot of music and energy. There were difficult times too, illness and some sadness, but I love my family and my history. I know it made me who I am, every bit of it.

NYFA: Have you always thought of yourself as an artist or was there a decisive time when you decided to be an artist?

DC: I think I decided to be an artist when I was 16, not a visual artist but a musician. I was athletic in high school and played on sports teams each season, field hockey, basketball, tennis. I loved sports and even thought I might like to be a gym teacher! That takes some people by surprise. And my parents were supportive. They wanted us to be ourselves and make our lives doing something we loved. And I really loved playing sports. One day on my way to the hockey field, I was crossing the road and was hit by a fast moving car. I was hurt very badly, my left leg bones broken in 2, so that put an end to those sporty dreams! My recovery took some time and I went from a very physically active social life to a sedentary and solitary life. It was quite depressing. But it was at that time that I got more serious about my music and started drawing more. I believe that bad accident influenced my life path. It made me think, and I after some depression and anger, I felt grateful. I went to college hoping to study music, and for fun, started attending life drawing sessions at a local art society and I just loved it. LOVED. I’m not really sure why this took me by surprise, but it did. And from then on, it was all visual art for me. I studied a lot of other things, but I think I knew that I would be an artist.

NYFA: Do you have a dedicated studio? What is your workspace like?

DC: Yes, my studio is in Greenpoint (Brooklyn). It’s a spacious studio in an industrial building on the Newtown Creek. But because I often work on site (drawing directly from life), I still often work at home. So my apartment and my studio are just blocks apart so I can move freely between the two spaces. Both places are my studio.

When I first moved to New York my studio was my railroad apartment. (I still live there.) I didn’t have a separate room that was my studio, it was just my apartment. I usually worked on the largest surfaces which happened to be my kitchen table or my bed. Like most apartments, it was always the same, but also always changing. Making dinner, drawing, sleeping, drawing. Drawing in those confined spaces affected my work. I didn’t have enough wallspace to make big works, so in order to make large works, I glued pieces of paper together and folded it as I went. In graduate school I had been an oil painter, working on large canvases, but working at home influenced my choice of medium, and I found more freedom in working on paper. By folding a drawing, the work became portable, and I could draw at the kitchen table, in bed, anywhere. Some people choose to work in modular ways, I tend to paste and fold.

NYFA: Many of your drawings are done of interior spaces from films, can you tell us about your work’s relationship with film and why you select certain films, moments, camera movements?

DC: My history of working with film goes back to college days when I was studying and writing about film. Back in the 80s when we studied film, we attended special screenings, and I think we watched each film twice. Films were projected, and there was no borrowing the film or rewinding, and so in order to write our papers we had to take notes in the dark like mad. I developed a way of writing in the dark, without looking at my paper, writing with one hand, and guiding my place on the page with the other, all by touch, because I didn’t want to take my eyes off the screen. It took some effort to decipher some of those notes! The note pages were combinations of dialogues, observances, and some sketches of frame compositions. I LOVED the cinema, and through this writing and drawing, I became familiar with its construction and language. I was analytical and critical, but always a fan.

One genre that was of special interest was melodrama. Many film scholars were reviewing and re-reading films from cultural perspectives and the so-called “women’s picture” was of great interest. In films, meaning is conveyed through the visual and audible and through all aspects of production, not just the “story.” For a while, I drew the women from these films, like a kind of a word salad of text and images: the way they looked and the things they said. Reading back my notes I found that the ways actors speak in the movies is very different from the ways people speak in “real life.” I was interested in the ways people and places are represented through narratives that appear seamless, but that are in fact complex collages of fragments.

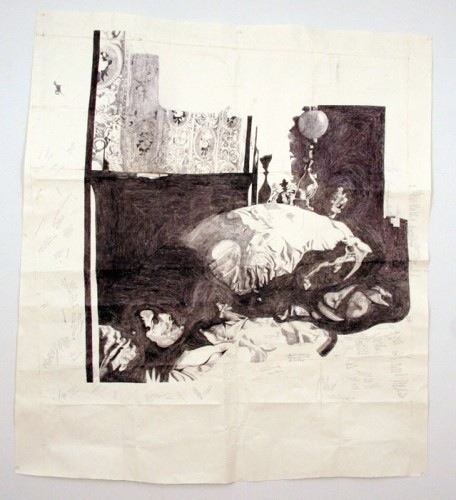

In the studio I was making big baroque still life paintings. Eventually when working at home, I’d draw and paint images of the objects on my kitchen table. Often the television would be playing while I worked, mostly soap operas and daytime talk shows, and sometimes I’d transcribe things I heard and saw on the tv directly into the still life drawing or painting. I drew the visual and the audible, my immediate domestic physical space and the fictional domestic dramas of melodramatic stories, all in the same drawing. At that time I started using ballpoint pen in my work, thinking that it might make sense to use this common writing instrument. I liked the idea that the pen I used to make shopping lists could be my art material. And I noticed that many of the melodramatic movies and soap operas take place indoors. The narratives often involve families or lovers in crisis, and often are set in domestic interiors. I often say that even though the front door is unlocked, somehow no one can leave. Everyone’s stuck in their roles. I used to think the women were the only ones stuck, but EVERYone’s stuck, the women, the men, the kids. Everyone’s trapped. And so I started to think that I needed to look into the places the characters inhabited. At that point I decided to take out all the figures and just draw the places. I looked for films from which I could piece together a panoramic view of a room. Occasionally the camera pans an entire room, but usually I have to find the parts of the room from many different shots in the film. I locate the different shots, and piece them together through drawing to reconstruct the room as a panorama. This is all technical process information and maybe not so interesting. But essentially, I am taking the film apart and rejoining it through my drawing. The lens of the camera becomes the viewer’s eye, and I go with it .

Sometimes the camera puts “us” in uncomfortable positions, for instance, as a woman viewer it can be disturbing when we assume the point of view of a male stalker (i.e., camera follows a woman down a dark path). The eye of the camera is powerful and interesting. It can be distant or close, removed or highly personal.

While the camera’s movement is captured on paper in some of your drawings, your own perspective becomes apparent in your drawings of interiors from life. Do these two different captures of “gazes” have different meanings for you?

When I draw from life I draw environments I occupy. My gaze is focused and observant, but also mobile. Viewing, writing about and drawing from the movies has made me think about the ways I frame, remember and record my experience in the world. No matter how naturalistic my drawings may seem, they are 2-dimensional abstractions of a 3-dimensional world. Black and white abstracts too. The gazes shift, vanishing points accumulate and I hope express my movement through space and time. Even if the drawings are composed of many shifting points of view, I strive to join the fragments to construct a representation of a slow seamless movement.

NYFA: Other artists have referred to inclusion of an abundance of detail as “a meditation” and as “self-punishment.” How do you feel as you begin a highly detailed work or section of intense detail?

DC: This is interesting, and I can understand what they mean. I don’t think my work is meditative or self-punishing. I will admit that I do not find drawing “fun.” I think I just like to see deeply, and for me it is a kind of knowing, a kind of travel, visually “crawling” across a table top, “climbing into” a flower. And when I get an idea, I just need to see what it looks like on a paper, no matter how labor intensive it may be. There is a huge difference in the kind of detail I can obtain from working from film vs. working from life. I love the difference. When I work from film I work with what I am given. A film is a series of moving photographs, and while we may be able to identify people, places and things as the film rolls, when we freeze a frame, sometimes the details are not as clear as we remember.

Photography abstracts the world. We understand how to read an image, and so we may see an image of a chair, and accept that there’s a chair leg in the shadow, but really, maybe the shadow is so dark that we cannot see the leg. So the IS no leg. It’s just a shadow. And that’s all we get. We just assume the leg. So when I draw from film, sometimes I don’t understand the “object” I am drawing. Sometimes I just can’t read it. The lights and darks are just shapes.

Drawing from life is very different. If I wish to draw a dramatically-lit still life from a certain distance, maybe the objects on my table will also be obscured, but I can choose to look closer. I can choose to change the lighting, I can see every detail in the crack of a vase or not. Everything is accessible. There is a painting by Salvador Dali of a basket of bread on a white cloth from the 1920s. I find it such an odd painting because even though the framing tells us that the basket of bread is at an arm’s length from us, the details in the objects are so intense that it feels that we must be looking at it much much closer. This is something that is possible when working from life. We can see from afar and up close at the same time. As artists we can share this experience and take the viewer with us on this search/travel.

NYFA: Do you have any advice for emerging artists?

DC: This is a very difficult question for me because I guess I have a lot of things I could say, but today I’ll just say that if you really need to be an artist, then work hard and work every day. All days won’t be good.

Intentions may not be realized, but pay attention to these unintended results too. Pay attention to your failed work. Sometimes it’s better than what you intended. Sometimes we think we have failed just because we haven’t realized our intended goal. Sometimes we make things we’ve never seen ourselves do before, make “mistakes” and that feels wrong, but look at it and think about it before dismissing. Don’t be afraid of what you don’t immediately recognize.

We all have a deep well of things inside us, and some of it isn’t pretty, but is powerful. And don’t be afraid of the pretty either. There can be a power there too. Sometimes we get distracted, stray, get lost, but that too can be very good. Wandering can be very productive and it is valuable to record this movement in whatever medium you choose.

As artists we are observers and readers of our world(s). Things do not always go well. Sometimes things are really good and sometimes it seems that no one cares about you or your work at all and that feels terrible. But I suggest trying to stay open, and to keep sharing your work with others. Sometimes a curator who does not select your work for one show puts you in another show or recommends your work to someone else. Rejection does not automatically mean your work is bad. Think about things people say, but you don’t have to accept it. Be honest in your work, in what you mean to say and be true, not stubborn, but true. Keep your eyes and ears open. Listen and hear and consider, but don’t obey.

These sentiments are pretty corny, and even as I write them I understand they sound like a phony pep talk, but I really do believe all this. There were about 10 years when it felt like no one was interested in my work. I had had some early “success” and then it vanished. Like I just said, it seemed no one was interested. But I kept working and I kind of thought I might never show my work again, but I kept working. And for me, that may be when I really understood I was an artist, not when I was showing, but when I WASN’T showing. This isn’t for everyone, that’s for sure. I was timid and maybe if I’d tried harder I could’ve gotten someone interested, but it’s ok. I don’t regret too much, even the bad times. All our experiences make us.

NYFA: You wrote in your artist statement to NYFA in 2005 (the year Clements received her Fellowship): “I’m interested in melodramatic figures, language and spaces.” Has this changed at all? Is this still the first sentence of your artist statement?

DC: What an interesting question. Yes, my statement has changed. As you can tell from my answers above, I still think about the things I wrote in 2005, but I have changed the focus a little. My most recent statement begins:

“Working primarily on paper I draw from the spaces of my immediate environment and the visual spaces of cinema.” It continues, “My works range from room-sized panoramas to small framed works. Subjective views of the world, their meanings and forms, are central. I make images of what and how I see, hear, and touch in a world that resists framing and where nothing is fixed. Each perspective in my drawings is local, almost never an overview.”

Learn more about Dawn Clements here.