Spotlight: The Laundromat Project

The Laundromat Project’s Create Change Public Artist Residency artists Michael Premo and Rachel Falcone’s installation at Wash and Play Lotto Laundromat in Fort Greene (2009)

No matter where laundromats are located, be it in Brooklyn, Queens, Harlem, or any other small town or large city, time spent inside of a laundromat is often a process of waiting for the coin-op cycles to be completed, the air thick with the sweet smell of detergent, humidity, and the constant rumbling of machines. It is in some sense an in-between time, where neighbors might brush up against each other while folding their clothes or waiting for their load to dry.

The Brooklyn-based arts non-profit The Laundromat Project (LP) has sought to activate such mundane sites of necessary routine into rich community spaces with a focus on enriching low-income communities of color through guaranteed access to art and culture.

Blueprinted by founder Risë Wilson in 1999, the LP has been bringing arts programs to local laundromats in and around New York City with the understanding that creativity is a central component of healthy human beings, vibrant neighborhoods, and thriving economies. Operating at the intersection of art, social justice, and entrepreneurship, the LP has been awarded a prestigious Echoing Green Fellowship, which recognizes it as one of the most innovative social enterprise start-ups in the world.

When the LP first began, Wilson found it challenging to gather institutional support for a mission that crossed sectors, so she asked herself, “Did I want to use up precious start-up capital and momentum figuring out how to convince people of the importance of art, or did I want to get on with the mission and vision?” Fortunately, she chose the latter and launched two core programs: Works in Progress (WiP), free arts education workshops designed for a Harlem community, and the Create ChangePublic Artist Residency, comprised of public art projects designed by artists of color that engage their neighborhood coin-ops. Both WiP and Create Change intentionally stage participatory art-making in spaces outside of the rarified, often elitist settings of galleries and museums (which usually charge exorbitant entry fees) by using the laundromat as the central interactive space for convergence and creativity within the neighborhoods engaged by the LP.

The LP’s belief in social equity and the power of the collective is reflected both in how they work with communities and how the LP team and staff build solidarity in shared responsibility. All feel invested in a generative vision beyond their individual capacities. This cohesion is also evident in the LP’s policy of “hiring locally to serve locally” in that the staff and board reflect the communities focused on by the LP and hold professional experience in sectors relevant to the organization’s mission.

Works in Progress

Every weekend afternoon from late summer to early fall, two folding tables and a selection of stools are set up in front of The Laundry Room, an otherwise ordinary-looking coin-op on 116th Street in Harlem. A colorful selection of materials—among them feathers, beads, faux-fur, scraps of cloth, glitter, glue, and paints―are arranged across the tables by The LP’s Works in Progress Coordinator Petrushka Bazin, along with teaching artists and volunteers who encourage passersby to pause, have a seat, and take part in an impromptu art-making project before continuing on their way to their weekend wash.

It was a particularly sunny, hot Saturday in August when we visited The Laundry Room, where a flag-making project meant to reflect one’s neighborhood was in progress. The flag, an emblem meant to connote national pride, is a loaded object for many in low-income communities of color who feel under-represented by federal interests. Although with Obama now in the White House, renewed hope in government is echoed on storefronts along 116th Street, which were plastered with colorful depictions of the president. Beyond notions of nationhood, pride in community was also palpably felt on the block that day. The flags we saw spread across the tables were decidedly colorful and upbeat with African and Caribbean influences. The tables were sheltered beneath two trees, and we sat between children from the community, thoroughly immersed, earnestly and gleefully, in flag-making.

A Works in Progress workshop in front of The Laundry Room in Harlem

WiP offers a sustained, three-month-long engagement with weekly projects conceived by Bazin along with the WiP teaching artists, Ifétayo Abdus-Salam and Alexandra Tyson, all of whom are Harlem residents with extensive experience in arts education. Bazin recalled the responses they received their first days stationed in front of The Laundry Room, their tables laden with art supplies. “People definitely approached us hesitantly. But once they got started on their projects they became very excited by the results. Others were baffled by us giving away free art classes on the sidewalk. ‘Wait, this is free?’ was a question we heard a lot.” For many residents in the community, art supplies are a luxury, and WiP’s explicit intention is to make art education and art-making available for all. Says Bazin, “We emphasize the idea of bringing art back down to the earth and in your backyard to provide accessibility. We want to foster a meaningful and rich relationship between artist and laundromat user in order to dispel any myths about what art-making is or who it’s for.”

Create Change

Each year, the Create Change Public Artist Residency offers professional training and a network of peers and mentors in the field to a select group of artists for the creation of socially engaged public works. When the 2009 residency cycle began last summer, the three resident artists–Carlos Martinez,Michael Premo (in collaboration with Rachel Falcone), and Tracee Worley—regularly gathered with LP staff Wilson and Bazin for potlucks at various host locations. They shared resources and the progress of their projects as well as participated in professional development sessions with established artists, curators, and other figures in the field. These gatherings provided a vibrant nesting ground for the artists and guest collaborators to share and generate new ideas.

Following the LP’s mantra of working locally, the Create Change residency asks artists to develop community-rooted projects in their own neighborhoods. Yet the residents this year had varied takes on rootedness: native New Yorker Premo was the most grounded with an installation at his neighborhood establishment Wash and Play Lotto Laundromat in Fort Greene, Brooklyn; followed by semi-nomadic Martinez who traveled with his portable photo booth through a circuit of six different laundromats in Jackson Heights, Queens; and finally, the roving Worley who, with the help of friends, let loose a free-for-all flyer bombardment of more than 50 local laundromats from Brooklyn to Manhattan and beyond. In addition to their individual interventions, these artists are currently featured in the Create Change Artist Residency Exhibition at the alternative space SUPERFRONT (October 17-December 12, 2009), co-organized by the gallery and the LP.

All the artists gathered testimonies from community members whose voices would otherwise not be heard in this intimately poignant way. Their themes unfolded from asking neighbors to share various aspects of their lives and community, which required varying degrees of trust. The artists’ engagements, thereby, tapped into the nuances of everyday life and, at times, shifted perceptions by their very provocation.

Premo and Falcone’s installation (October 23-November 2, 2009) was part of a larger project called Housing is a Human Right, an ongoing multimedia documentary portrait of the struggle for home in New York City, which the duo is developing as an innovative advocacy tool to be shared with other community-based and national partners. Through photographs and audio recordings, the installation featured portraits of underserved neighbors of color. One can step away from the laundry and meditate on one of the six photographs hanging above a row of whirring washers while listening to the remixed soundscapes of stories and abstract samplings. (The sounds came from two audio speakers installed in the front and back of the laundromat.) When a grandmother from Guatemala was asked what she thought of the pictures and stories, she responded with her own questions: “Where are these people now? Are they being fed? Sheltered?”

In their interviews with neighbors, Premo and Falcone found that the complex layers of displacement recounted were like an ever-shifting dance, moving beyond mere physical loss of home. They highlighted the “super arc” of each story and arranged them into couplets with themes such as disaster, economic dilemmas, and the psychological and emotional shift from isolation to social inclusion. One gay neighbor shared the challenges of caring for his ailing HIV positive partner and how the simultaneous fight to keep their apartment with other building tenants gave him renewed strength and purpose for a greater good. And so, underlying these tales of disruption, there is a hopeful message of defiance and empowerment in the face of adversity.

Throughout the fall, Martinez set up his portable photo booth outside of laundry establishments such as Aqua Clara Laundromat in his neighborhood of Jackson Heights. Reminiscent of a traveling vaudeville act, Martinez pulled heavy black curtains and backdrops out of a trunk in order to set the stage for ushering people into his booth to take their portraits and interview them about their neighborhood. His sitters often hailed from other parts of the world like Central and South America, as well as East and (to a lesser extent) South Asia. Not surprisingly, the Latino neighbors were most comfortable with the Colombian photographer.

Martinez taking a portrait in his photo booth: His backdrops include a vintage fabric of rose print, a map of the world, and a collage of calling cards reflective of the linguistic diversity and ethnic connections to home of his immigrant neighbors in Jackson Heights. Photo by Hrag Vartanian.

The themes that Martinez culled from neighbors’ testimonies were urban planning, environmental justice, community development, and cultural identity/diversity. Addressing these issues, people suggested more green spaces, libraries, cultural activities, and after-school arts programs in Queens. In response, Martinez has found that there are many artists who are willing to volunteer their time to meet the cultural needs of the Queens community. But the political will is first needed to develop cultural activities in his neighborhood. To stimulate this will through advocacy, he will soon present his project to the local community board.

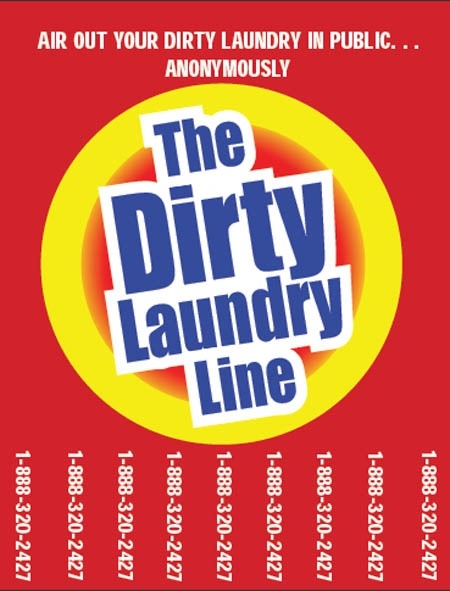

Drawing inspiration from the Situationists and other urban interventionists, guerilla artist Worley roamed the streets of New York’s boroughs, flyer-bombing bulletin boards at numerous laundromats. Each flyer is like a hi-jacked version of the target logo found on a box of Tide. Its message is clear: customers are called to ring The Dirty Laundry Line (888-320-2427) and anonymously “air out” their dirty laundry or voyeuristically listen to what’s been voiced. The archived messages can also be heard on Worley’s website.The artist tapped into the potential for openness in what she views as the public yet intimately awkward space of a laundromat where people often avoid each other in the private act of handling their unwashed intimates. Messages ranged from confessions of love and infidelity to transgressions in the workplace and causes of the swine flu. But clearly there is still a ways to go in washing out all the dirt. As Worlee admits, there are currently more voyeurs ringing the Line than purgers of sin.

With this downloadable flyer on Worlee’s website www.thedirtylaundryline.com, the artist invites interested parties to flyer-bomb their own neighborhood coin-op and be part of her web of interventions.

For the next Create Change residency cycle, the LP will release its call for proposals in January 2010.

Expanding on the Mission

The LP has ambitious long-term goals, among them the purchase and ownership of its own laundromat art center where public art and art education programs would be consistently offered to the public, and would provide a more sustainable social enterprise model for the organization itself. “The purpose of the social enterprise element of our revenue model is in service to the mission,” says Wilson, “so first and foremost our current priority is to scale up the impact of what we do and who we do it for. The sooner we have more human and financial resources that we can invest in planning and executing the launch of the business, the sooner we can pursue a real estate project.” To raise funds, the LP successfully executed its first benefit auction in November, with editions by Glenn Ligon, Wayne Hodge, Chitra Ganesh, Shinique Smith, Saya Woolfack, andMickalene Thomas. Tickets were refreshingly priced at the affordable rate of $25 to upwards of $1,000, in line with the LP’s focus on giving more access to the general public.

The 2009 Create Change Public Artist Residency exhibition opening at SUPERFRONT in Bedford-Stuyvesant (2009). Photo by Sara Zuiderveen.

First and foremost, the LP would like to grow the scale and impact of WiP by establishing in-school programs as well as expanding its out-of-school activities to include more drop-in workshops and courses that will connect art-making with larger life lessons. The LP is also setting its sights on deepening the impact of Create Change residency artists by making their public art projects into longer-term engagements with neighbors and neighborhoods. Other large-scale aspirations include the potential replication of the LP model beyond the five boroughs to other cities and countries throughout the world. Judging from the drive and vision of those associated with the LP, the seemingly humdrum space of the community coin-op will continue to evolve and elevate into universal sites of creative possibility.

Karen Demavivas is Program Officer, Immigrant Artist Project at New York Foundation for the Arts.

Suzan Sherman is the Editor of NYFA Current.