The Business of Art: A Conversation with Jackie Battenfield

Jackie Battenfield in the Derriere L’Etoile Studios, completing a set of woodblock prints.

As Jackie Battenfield points out in The Artist’s Guide: How to Make a Living Doing What You Love, business tactics such as planning, assessment, time management, and negotiation are seldom offered to artists in ways that are relevant to their individual practices. Lacking fundamental business skills, many of us ignore career strategizing in favor of fantasizing about gallerists and curators knocking down our studio doors and launching our careers for us. The Artist’s Guide reminds us that no one is coming to save us—that we must instead carefully plan for a successful, sustainable art career and overcome the doubts and fears that have the potential to derail us. Battenfield recently welcomed me into her Williamsburg, Brooklyn studio and shared with me her clearly defined approach toward career development for artists.

Amber Hawk Swanson: The Artist’s Guide is written from the perspective of having transitioned from running a gallery into making your living as an artist. Please describe your background and what brought you to writing this resource for artists.

Jackie Battenfield: In 1981 I started the Rotunda Gallery, which is a non-profit organization in Brooklyn. I had to learn how to do everything involved in running a gallery: curating exhibitions, fundraising, working with a board of directors, developing programming, and promotion. Along the way, I met my husband on a studio visit; we got married and a year later we had a baby. I had exactly two weeks maternity leave because if I wasn’t at the gallery, work didn’t get done. I continued to paint while I ran the gallery, but I was kind of a secret artist. I was hesitant to promote my own work while directing the gallery. By 1989 I was pregnant with my second child and I just couldn’t juggle it all anymore. I had given the Rotunda Gallery my best, but knew that for it to go further it needed new energy. I had learned a lot about the art world running the gallery, so I decided to take that information and apply it to myself as an artist and figure out how to make a living from it. Even though I was about to have another baby and the economy was in recession, I resigned and set off. Rather than look for one gallery to take care of me, I sought out a broad base of support for my work with a variety of art professionals throughout the United States. I pulled out the Art in America Annual Guide to Galleries, Museums, & Artists and read it cover to cover looking for opportunities. I interviewed friends in other cities, did my research, corresponded with lots of galleries, and received more rejections than one can ever imagine. But in time, I also found good people who wanted to work with me. Within three years I was making a living primarily from my painting.

During this time, the Bronx Museum invited me to take over the seminars for the Artist in the Marketplace program, (AIM) which was a perfect fit with my studio practice. AIM was my Tuesday night out away from the kids, a wonderful opportunity to work with a select group of emerging artists, and a place to talk about the issues we were encountering. I ran the seminars for sixteen years. In 2001, I was asked to join a team at Creative Capital to help design professional development retreats for their grantees and for artists around the United States. Through Creative Capital I’ve had the opportunity to work with artists of all ages, in big cities, small towns, and rural areas. There are challenges and rewards in all environments and that’s added to my education. Lastly, I designed and implemented a professional practices curriculum inColumbia University’s School of the Arts.

It was three years ago when I realized that no matter how many artists I taught, I couldn’t reach as many as I wanted, so I began to compile information into a resource book. I placed my studio work on hold to get this information into a form that would be accessible for artists everywhere.

AHS: What will artists learn from reading your book?

JB: I’ve put together a guide that any artist, no matter where they are in their professional life—in school, just beginning, emerging, mid-career, or starting over—can find answers to situations they will encounter. The book provides the essential tools for them to construct a road map to boost them to a sustainable practice over the long term. I show artists the structures they need to build into their daily life that will protect and nurture their creativity.

AHS: Your book includes a number of quotes by artists and arts administrators as well as images of many artists’ works. Please tell us about your selection process for the quotes and artists whose work you chose to include.

JB: A picture is worth a thousand words. I choose artists whose work I admired, found through research, or who were referred to me. Including artists’ work in my book does three things. First, an image helps me demonstrate a point. For example Rossana Martinez’s work beautifully accompanies the text passage: “If your installation has a performative element, make sure you have someone document that aspect as well. Remember, you’ll have only one chance to capture the images you’ll need.” This saves me additional words of explanation and I can move on to another subject. The second reason is that when I included quotes from an artist, I thought it would be helpful for the reader to get a fuller “picture” through an image nearby of their work. Finally, hey, this is a book for artists, don’t we all love to look at pictures? I know I do.

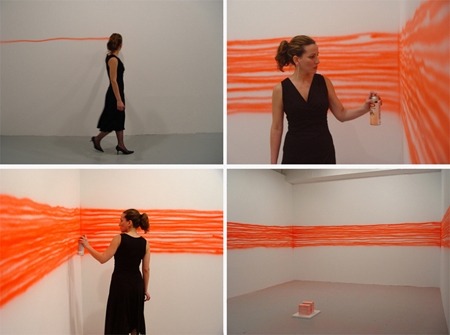

Rossana Martínez

Glow (2006)

Performance and site-specific installation at Hunter College/Times Square Galleries, NY

Fluorescent orange spray paint on wall

Edition of 1,000 fluorescent orange spray paint on white paper, 4” x 6”

AHS: You state in The Artist’s Guide: “…I have neither heard nor found any secret shortcuts to a thriving career.” Over the years, have you found artists have the misconception that there are shortcuts for their art careers?

JB: Hey, don’t we all wish there are secret shortcuts? I would like to find one too, but I haven’t. Yes, some artists come to a workshop or pick up a book hoping it includes the magic phrase that will make their work irresistible to a gallerist, curator, or critic. Or they hope “the right art school” or “the right party” will catapult them into fame and fortune. We have this notion that when you get gallery representation your problems are over. If you are selected for the Whitney Biennial your career is made. I think it’s only human nature that we wish there was a surefire way to success.

Just as there are no shortcuts to making significant works of art, figuring out how to manage and promote your career is a process developed through trial and error and honing your skills over time. The trouble is that many artists only want to make their work and hope someone will come to the rescue and take care of the business side. Well that’s just not going to happen. In any career there will be good and bad times. My book is about how to manage the ups, the downs, and all the places in between.

AHS: Determination seems to have gotten you through some of the personal challenges you faced along the way. How have you sustained your drive through the years and what advice can you provide to artists experiencing bumps in the road?

JB: Nothing is more powerful than a compelling vision of what you want to create. My first plan was to home-care my children and paint full-time. To do that I had to give myself “the Jackie Battenfield grant” to be in my studio every day. I then looked at what resources I had at my disposal to get started. Everyone will have their own particular vision of what they want to accomplish. If you don’t have one, it’s easy to run around in circles instead of moving forward in a meaningful direction. Your vision leads you and makes you take action. I have also been sustained by solid support from my husband and my arts community. They provided the platform from which I could jump off and take risks. So, nurture the key people in your life who you can rely upon when times are hard. They’ll help pick you up and dust you off so you can go out there again. It’s too hard to do it alone.

AHS: The questions I receive on the NYFA Source Hotline (NYFA offers a live toll-free hotline for the business and technical questions of artists across disciplines, 800.232.2789 3-5pm EST, Monday-Friday excluding holidays) often revolve around the subject of networking. Certain artists who call-in feel isolated by their geographic location and others feel as though the solitude they require in their studio practices is at odds with the networking they feel is required to move their careers forward. What advice do you have for artists on this topic?

JB: We all need varying degrees of solitude. I need a certain percentage of my week to be alone and then there are times where I’m dying to get out. Everyone can strike a balance between the two. Understand that networking is a skill that can be learned with practice. Start by going to a local event and introduce yourself to one or two other people in the room. Participate in what happens in your community to be connected in a more intimate way. These are not difficult skills; they just require you to be proactive. If one of your goals is to connect with more people, then you have to give yourself the assignment to do so. For example, I’m very shy. When I say this in my lectures, nobody believes me. They think, “Jackie Battenfield can do anything,” but that’s not true. I had to teach myself how to go to an art opening and not run out of the room before I’d spoken to at least three or four people. Practice makes it easier.

In the book I also discuss lots of ways artists can create their own community. If you have an Internet connection, you can build an online community. Maybe you are more comfortable e-mailing people or Instant Messaging. Develop your own critique or reading group. All you need to do is ask two other artists to join you in forming a group and have them invite others. Suddenly you have eight people and a whole year’s worth of studio visits. Form a collective, join a collective, participate in something that is happening locally, volunteer—there are lots of ways to get started.

Ellen Harvey

New York Beautification Project (details), 1998-2001

Oil on graffiti sites in New York City

Each 5” x 7”

Photo: Jan Baracz

AHS: An overarching theme in your book is the importance of ordering and structuring the business of art to buy time and space for your ideas to flourish, and yet it seems easy to lose sight of one’s goals in the midst of day jobs, familial obligations, and the like. How do you advise artists to continue to prioritize their art practices?

JB: When you have a vision of your life and have determined some long- and short-term goals, you have a list of priorities. It is then easier to sort the myriad tasks of your studio practice and daily life into those that take precedence over those that don’t. You can’t do everything, but if you first pay attention to what needs to be done that makes a difference. There is a beautiful quote by Janine Antoni included in the book, “All my decisions come from wanting to make art for the rest of my life.” Janine has clear priorities and it determines her actions.

AHS: You mention the concept of self-block and some of the emotional challenges that artists face when approaching the professional practice components of their art practices throughout the book. How does facing some of the emotional impediments that have the potential to derail artists factor into career strategizing?

JB: We put our heart and soul into making art, so everything around it feels personal, even when it’s not. These negative emotions are a powerful cocktail and they hold us back because they stop us from pursuing opportunities. Your job is to apply to available opportunities. You effectively reject yourself by not going after something that is appropriate for your art. Many of my AIM artists reported to me that they applied and were rejected several times before they got it. I’ve applied for NYFA Artists’ Fellowships for years, and have yet to receive one. It can be hard to get honest feedback about your application, or online submission, or grant proposal, and it’s also easy to think that you did it wrong if you were rejected. It all feels so personal. Look, I’m just as insecure as everybody else, but knowing what I want to accomplish has made me reach beyond my self-doubt and take the actions that I needed to take.

AHS: It seems basic, but I appreciate you noting that applying to opportunities is part of one’s job as an artist.

JB: You need to schedule time every week to research opportunities and to follow through on administrative tasks. You need to find a good time so that it doesn’t get in the way of your creative practice–even if you are working two part-time jobs and managing a family. I’ve done it.

AHS: What are some of the things you’ve found commonly hold artists back from achieving their goals?

JB: Isolation will hold you back from achieving your goals, as will taking rejection personally. Rejection is going to happen and you need to begin seeing it as another piece of information. I know how painful it is. Some rejections will hurt more than others. However “no” doesn’t necessarily mean “never”—it can also mean “not right now.” If you take rejection personally you’ll stop going after opportunities; your jealousy over your peers’ accomplishments will separate you from your community. It’s a downward spiral of negative emotions. Artists who are isolated hold themselves back from accomplishing goals. When you are all alone, it’s too easy for you to let yourself down. If you have a network of support, you’ll have helping hands to weather difficult times and put yourself back on track.

Kurt Perschke

RedBall: Barcelona, 2002, Jaume Street in Gothic Quarter

The Redball Project is a sculptural installation traveling around the globe.

AHS: How should the current economic downturn factor into artists’ career strategies?

JB: Well, first of all I want to make it clear that my book is about the stuff artists need to pay attention to, no matter if the economy is up or down. It’s just as important to have goals, to go after opportunities, to nurture relationships, and to figure out a manageable financial and organizational structure when times are good or bad. My book is about life skills that help people maintain their practice in any economy. Even during the best of times one artist can have a show that doesn’t sell and another artist will have multiple opportunities during an economic recession. Nothing is static; every year the art world changes. Developing a network of peers and professional relationships helps keep you current and puts you into an information stream concerning tips and opportunities. When I started out on my path in 1989, I started to read the financial section of the New York Times. I wanted to know what was happening economically throughout the United States. I started subscribing to art magazines that were not New York-focused because I was looking for opportunities throughout the U.S. With the Internet, it’s easy to get information that is broadly based and to look for new strategies to connect your work with an appreciative audience. It’s not whether things are good or bad but what the best approaches are right now in the art world.

Jackie Battenfield is an artist and the author of The Artist’s Guide: How to Make a Living Doing What You Love, a NYFA fiscally sponsored project just out from Da Capo Press. For over twenty years Battenfield has supported herself on the sale of her own artwork and teaches career development programs for visual artists at the Creative Capital Foundation and Columbia University.

Amber Hawk Swanson is Officer, NYFA Source and an interdisciplinary artist.