The Business of Art: Making Space

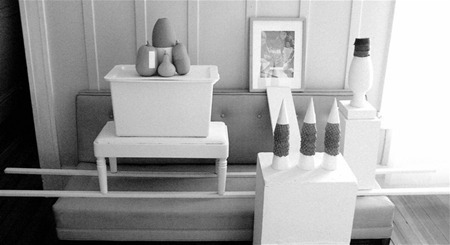

John Well’s Ave Lux show at New York City’s Honey Space (May 14-June 13, 2009)

In the Hyde Park Art Center’s recent Artists Run Chicago—a cacophonous, multimedia exhibition of the city’s artist-run spaces and the art they’ve hosted over the last decade—a stack of posters by the former gallery Deluxe Projects gives a twelve-point guide to running a DIY art space. Step 1: “Fall in love with art,” it reads. Step 3: “Find other artists there who are as desperate as you are to explode into the world!” Step 7: “Spend every day and night sanding, spackling, painting, and coughing up drywall dust. Paint your friend’s head!!! Ha!”

The poster, with its wonky blend of idealism and tongue-in-cheek practicality, captures an energy typical not just of Chicago’s art scene, but of a whole movement of artist-run spaces that has been gaining ground over the past year.

The artist-run model is not new: New York famously had Gordon Matta-Clark’s restaurant/art collective Food in the 1970s, and cities like Chicago and San Francisco have long had vibrant alternative art scenes. But in a culture buffeted by the vagaries of economic recession and increasingly permeated by DIY ideas, there is a new energy for the artist-run approach. Britton Bertran, who co-curated the Artists Run Chicago show, says that right now alternative spaces are booming. “In this market…a lot of the [commercial] galleries have to be cognizant about what they’re showing as merchandise that can be bought off the wall,” he explains. “Commercial spaces are plummeting at a huge rate, while alternative spaces are opening at a huge rate.”

But Bertran cautions against explaining the recent surge in artist-run projects in relation to the economy alone. “The Chicago art world has this funny way of operating in waves of half-decades,” he says. “Every five years or so there is a slew of artist-run spaces that pop up all over town.” But it’s clear that the recession, like any crisis, has forced a collective sense of urgency and awareness. In reflecting on their artist-run projects, several artist-curators from New York, Chicago, and San Francisco discussed the challenges and logistics of defining a new kind of space, and what a future artist-run world might look like. As Austin Thomas of her recently shuttered Brooklyn space Pocket Utopia explains, “I wanted to put artists back into the equation.”

“Pool open” at Chicago’s Swimming Pool Project Space (2009)

Making Space

Redefining that equation is, at its most basic level, a political act. “What made this possible,” says Jay Henderson, cofounder of the New York endeavor HKJB, was “artists and art world people getting sick of institutions dictating the terms that art is received on.” Those institutions—the museum, the commercial gallery, the rigid scalpel of theory—have assumed a dominance that seems, to many, out of joint with the way that art is actually produced and received. Brion Nuda Rosch, who started Hallway Bathroom Gallery (now Hallway Projects) out of his San Francisco apartment in 2005, notes that as an artist, “there’s just a way that I breathe with the work that a curator at a museum or someone in a commercial space” does not. In many of the artist-run spaces, the terms are decidedly artistic ones, blending exhibition venue with studio space (through an ongoing artist residency, for example), or conceiving of the gallery as a creative site unto itself.

Redefining the equation is also a chance to push the aesthetic experience into the physical space—to “make space” in a way that is more profound and pervasive than the traditional gallery allows. Thomas Beale’s New York Honey Space is a small alcove of a gallery on Eleventh Avenue in Chelsea where the sculptor has been alternately working and presenting shows since 2008. In commercial galleries, he says, the idea is that the white walls “disappear, and the work is what you see…but I don’t think that’s really true. I think that [the space] does shape your experience of the work.” In Honey Space’s current exhibition, John Wells’ Ave Lux,the installed curving walls call to mind the rounded space of a baptistery or the adobe hut of a desert ascetic, underscoring the spiritual ambiance of Wells’s gnostic, scribbled scrolls. “I’ve started to really think of the space less like a gallery and more like an artwork in itself,” says Beale. “The metamorphosis [from show to show] is part of the identity of the space. And…beyond the metamorphosis, physically the shifts in sensibilities from one show to the next are part of a larger story.”

Chris Sollars, founder of the apartment gallery 667 Shotwell in San Francisco, is likewise interested in those larger stories, and how the work and its environment interact. Sollars is intrigued by the way “people let their guard down” in the more relaxed space of a home. “It allows another dynamic to happen,” he says, “art in relation to life.” He has moved increasingly toward hosting time-based projects, such as video showings and events, as well as work that is explicitly about architecture and domestic space, two strands of practice that speak eloquently in the semi-private, semi-public realm of the apartment gallery. Other projects have moved beyond the physical confines of the apartment. As part of the 2003 work Start…Finish, the artistMark Shunney had the gallery’s address, “667,” painted at local auto body shops in the neighborhood. “So some of these projects,” Sollars comments, “kind of leave the house and they come back in,” inscribing new paths as they do.

Rico Gatson’s Systemic Risk Funky Revolution, from Brooklyn’s Pocket Utopia’s closing group show,Finally Utopic (June 6-28, 2009)

Finding Space

Artist-run spaces tend to pop up wherever there’s extra room: in empty garages, someone’s living room, an artist’s studio. For Rosch, the precipitating factor in converting his hallway and bathroom to art space was the closure of his commercial gallery in the Mission, a casualty of increasing rents. At first, Rosch was on the lookout for other gallery spaces to host the year of programming he had already lined up. But “then I started looking at my home and the events and happenings and parties that we’ve had here,” he explains. “It’s got great light, and it shows art really well. And I just came up with the simple idea of doing things in our hallway and bathroom.” Using living space for the art display has meant a great deal of flexibility for Rosch. “Not having overhead, I’ve been able, when I feel ambitious enough, to do something within the space… [I can] also step away and not be as active, and maybe be more active online.” Another tactic is exploiting fallow spaces or places in transition—where rent, by some fluke or act of goodwill, is cheap or nonexistent. Honey Space, for example, resides in a Chelsea building slated for eventual condo development, and was made available to Beale directly from its art-patron owner; the storefront that housed Pocket Utopia in Bushwick is owned jointly by Thomas’ husband, effectively cutting her rent in half.

Of course the ability to find and adapt spaces for art depends heavily on the landscape of each city. Bertran notes, “Chicago is like the perfect storm: great schools, peer encouragement, cheap rent, a solid history and some great physical spaces.” The storefront rent for Swimming Pool Project Space in Chicago is comparable, says co-owner Liz Nielsen, to local studio rents, and she splits the cost with partner Josh Kozuh. San Francisco, too, is marked by a profusion of great art schools and a sturdy nonprofit network, but its real estate is much more congested. “New York has more opportunities in terms of actual spaces,” says Sollars, spreading, for example, “way, way out into Brooklyn. Real estate doesn’t exist in the same way in San Francisco.” Courtney Fink, Executive Director of the San Francisco arts organization Southern Exposure, which funds many artist-run projects through itsAlternative Exposure grants, concurs. “There’s not lots of empty space everywhere,” she says, which helps explain why the apartment gallery predominates here. Ten or 15 years ago, she adds, there may have been more opportunites for storefront spaces in the city; but now, it’s “too expensive, too tight.”

Of course, flourishing in the margins is a risky place to be. Artist-run spaces are susceptible to a host of outside factors, from rents to zoning ordinances to changes in ownership or property values. Nielsen, for example, notes the recent crackdown on some Chicago apartment galleries, found to be in violation of zoning laws and city code. HKJB for one has embraced this very quality of the temporary and ad hoc, setting up each exhibition wherever it finds the space: their first show was held in cofounder Benjamin King’s studio, and an upcoming one is planned for an empty dock in Red Hook, Brooklyn this summer. Says King, “Deciding to just do the [first] show and worry about the space later really helped us to get out there and talk to people and get them interested in showing work with us.”

The Portable Ice Cream Stand (Assemblage Study) in the Living Room of San Francisco’s Hallway Projects (2008)

New Networks

Perhaps the most important thing about the artist-run gallery is the larger metaphor of space that it engenders: the idea of a locus, a forum, a place of social and artistic interaction. Swimming Pool, with its glossy blue floor, evokes a watery pool in a way that Nielsen hopes will “inspire conversation about art…When you’re inside an environment, like a pool or a park, ideas happen, ideas that wouldn’t necessarily happen other places.” Austin Thomas compares the nested layers of social space at Pocket Utopia to the “three chairs” Thoreau built at his Walden Pond cabin, “one for solitude, two for company, and three for society.” As an artist, she says, “you make art for yourself, you make art for other artists, and you make art for something a little bit bigger.” Pocket Utopia functions as the seat of those interlocking layers, and one in which the ties are strong. “I was always in the art world community,” Thomas adds, “but I never had my own community until I did this.”

Maintaining and forging those communities is key. King notes that, in addition to their role as exhibition venues, such spaces “provide a convenient and casual way to maintain consistent contact” with like-minded artists. Nielsen speaks of “hubs,” venues like Swimming Pool that provide connection points. While locally grounded, such hubs are continually expanding. “A lot of these circles have really closed together in the last few years,” says Rosch. “There’s now people I’m in touch with in Boston, Chicago. These circles are really tightly winding up.”

Just how long the current artist-run wave will last, and what role the economy will continue to play, is up for debate. Thomas is careful to acknowledge that the boom market, despite its flaws, was a helpful backdrop to projects like her own: “It wasn’t all good, but we all benefited somehow.” Says Courtney Fink, the art scene in general these days is “really brutal. There are places closing all over the place.” She hopes that the recession precipitates new systems for making art, although she notes, “I haven’t fully seen that materialize just yet…, this huge, revitalized artist-run world. [But] it has the potential for that to happen.” In the meantime, there’s one thing that everyone agrees on: now is a great time to make art, and artist-run spaces are playing a key role in displaying, and inspiring, fresh work.

Emily Warner is a New York-based critic and writer, and former Editorial Intern atNYFA Current. Her previous work has appeared in Newcity, Proximity magazine,BOMBLog, and Artcritical.com. She is a frequent contributor to The Brooklyn Rail, and a 2009 participant in CUE Art Foundation’s Young Art Critics program.