The Business of Art: Fair Use and Copyright Law

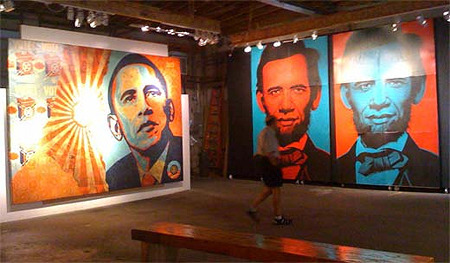

Shepard Fairey. Obama Hope Mural. From the “Manifest Hope” show at Andeneken Gallery. Democratic National Convention, August 25-28, 200

Copyright law made headlines recently when The Associated Press demanded credit and monetary compensation for a photograph referenced by artist Shepard Fairey for his illustrious Obama HOPE poster. Fairey’s attorneys subsequently filed for a declaratory judgment on the matter, seeking to vindicate the artist’s rights in regard to the works he created to support the candidacy of President Obama by arguing that it is protected under copyright law’s doctrine of fair use.

In a Huffington Post blog entry on the subject, attorney Jonathan Melber clearly describes the four factors used to determine fair use as, “what, exactly, the original work is, how much of it you’re using, how you transform it, and whether your new work hurts the commercial market for the original.” Furthermore, he notes, “…the transformation that really matters is the conceptual one, not the physical one.” Indeed, the complaint filed by Fairey’s attorneys contends that Fairey used the photo “as a visual reference,” which he “altered…with new meaning, new expression, and new messages.”

Many artists are following the Fairey v. The Associated Press case as it unfolds and are considering how the transformation factor of fair use pertains to their work. Although her fair use concerns are decidedly different from Fairey’s, Stacia Yeapanis is one of those artists. Yeapanis creates photographs, videos, and embroidery that often quote from mass-media sources in order to comment on the significance of cultural participation. Her recent video, We Have a Right to be Angry, embraces the impassioned genre of fan-made music videos, or fanvids, of edited clips from television shows. Yeapanis’ fanvid-inspired video includes appropriated footage from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Xena: Warrior Princess, and Charmed, all edited to “Invincible” sung by Pat Benatar. In July 2008 she uploaded the piece to the video-hosting service YouTube for both her art and TV-fan communities to view.

Several months later, on December 1, Yeapanis received a “takedown notice” from YouTube stating that Fox Broadcasting had blocked her piece using an automated video ID system. After being faced with the option to remove her video or dispute Fox’s claim, thereby consenting to litigation, Yeapanis began researching the takedown procedures outlined by the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998, which provides “safe harbor” from litigation to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) like YouTube, so long as they respond to third-party claims of copyright infringement in a timely manner. Yeapanis also contacted Chicago’s Lawyers for the Creative Arts. Intimidated by the potential costs of going to court, she has since removed the video from YouTube. In a recent interview with NYFA Current she stated, “Fox identified my video as infringing by using an automated system that scans for exact matches of audio and video fingerprints. This technology cannot take fair use into account. It cannot take the meaning of the appropriation into account. It doesn’t know about the history of art or fanvids. It is unlikely that anyone at Fox ever saw my video and evaluated it as only a human can do. In this sense, ‘fair use,’ as it is meant to function under the law is being eroded.”

Jonathan Melber, who has coauthored the forthcoming book, ART/WORK: Everything You Need to Know (and Do) As You Pursue Your Art Career (March 2009, Free Press), spoke with NYFA Current about the inherent imperfections of using an automated system for identifying potentially infringing material, noting that a fanvid would most likely be akin to a “false positive.” It is important to note, however, that because the four factors used to determine fair use are legally defensible positions and not a clear set of bright line rules, whether or not a fanvid such as Yeapanis’ would be protected under fair use could not be determined for certain without a court ruling. He states, “Even the best lawyers around will have to tell you ‘this is my opinion but we really won’t really know unless we take this to court.‘”

For most artists and fan vidders, going to court against a large and powerful corporation is financially impossible. Stacia Yeapanis feels that the takedown notice process, as outlined in the DMCA and in copyright law in general, must adapt in order to address fair use in a remix culture facilitated by digital technologies. She states, “The language in the notice is extremely intimidating for YouTube users. It’s an ultimatum. No individual wants to consent to being sued by a huge media corporation. And it doesn’t acknowledge the existence of fair use at all.” For some, like Fred von Lohmann, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), this process is equivalent to censorship. In his recent EFF blog post, he calls for YouTube to fix the Content ID system to not block videos, “unless there is a match between the video and audio tracks of a submitted fingerprint.” He also notes that if you are a YouTube user that would like to counternotice “but are afraid of getting sued, [EFF would] like to hear from you. We can’t promise to take every case, but neither will we stand by and watch semi-automated takedowns trample fair use.”

Stacia Yeapanis. We Have a Right to Be Angry (2008). Video still from fanvid, 5:10 minutes

Even in cases like Shepard Fairey’s, where potential copyright infringement is identified by human beings and not by software systems, Melber notes that copyright law is “not cut and dry. The thorny part for people trying to live by the rules is that the rules are general. The fact that they are general makes it very difficult to know if you are on the right or wrong side of the line.” He points out “a persistent misconception in the art world is that if you change a certain percentage of a photograph, for example, you are in the clear. This is completely false.” Yeapanis remembers learning this “percentage” rule in art school. She was taught that if an image is changed by 30 percent, then it is protected by fair use. The 30 percent transformation misconception relates to the visual nature of nonmoving images and does not address the transformation of edited appropriated video, but it is an idea that many artists across disciplines have learned over the years. Melber states, “The most important thing for artists to know generally, is that there is no such rule as ‘change something 30 percent and you are fine.’ The problem is that too many artists are taught that and then rely on it, but it is basically bad legal advice.”

Instead, Melber advises that artists spend some time understanding how the four factors used to measure fair use function and relate to one another. He points out that the four factors, all of which are based on previous rulings, are listed on the Stanford University Libraries’ Copyright & Fair Use website. For his Huffington Post blog entry, Melber translated the factors into plain language. Artists interested in further investigating the “measuring factors,” however, should study the descriptions outlined by Stanford. Much of the fair use content on the Stanford website is credited to NOLO, whose website includes a section entitled, “The ‘Fair Use’ Rule: When Use of Copyrighted Material is Acceptable.” Jonathan Melber also cites local chapters of theVolunteer Lawyers for the Arts (VLA) as a resource for artists seeking copyright law and fair use information. Additionally, both local arts councils and chapters of the VLA often host copyright and fair use workshops. Melber recommends interested artists attend as a way to supplement online research.

Shepard Fairey and his attorneys currently await a ruling in the early February declaratory judgment they filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The complaint can be found here. The case will no doubt continue to be widely publicized and appropriation artists like Stacia Yeapanis will surely continue to follow it. Yeapanis, whose work will be featured in the forthcoming book MP3 Volume II: Curtis Mann, John Opera, Stacia Yeapanis (May 2009, Aperture/MoCP), is unsure how to proceed with her fanvid-inspired video work. She told NYFA Current, “Part of me wants to try and change the law, the other part just wants to get back to making art.” Yeapanis still can’t afford the potential costs of going to court and has concerns about being part of a case that would establish a negative precedent for either fan vidders or appropriation artists should she have the opportunity in the future. She states, “My plan right now is to participate in the discourse.” She encourages artists to “stay aware of what is happening with creative nonprofessionals and ‘fair use.’ Pay attention to how often you go to show your friend a wonderful video you saw on YouTube and it’s gone. Even artists who have nothing to fear when it comes to copyright infringement should be concerned that creative expression is being stifled online.”

— Amber Swanson

More information on fair use and copyright can be found in the following NYFA articles and related websites:

Dr. Art on Copyright and Fair Use: An overview of copyright basics, fair use, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), and the Sony Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (SBCTEA).

Copyright, Fair Use, and the New Borrowers: A description of New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice 2006 status report on copyright laws titled, Will Fair Use Survive? Free Expression in the Age of Copyright Control, paired with a breakdown of contemporary appropriation-based work.

Center for Social Media: American University’s School of Communication hosts theCode of Best Practices in Fair Use for Online Video, that helps creators, online providers, copyright holders, and others interested in the making of online video interpret the copyright doctrine of fair use.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF): EFF’s main goal is to educate the press, policymakers and the general public about civil liberties issues related to technology; and to act as a defender of those liberties.

Chilling Effects: Chilling Effects is a joint project of several law school clinics and the EFF to protect lawful online activity from legal threats.

Creative Commons: Creative Commons is a nonprofit corporation dedicated to making it easier for people to share and build upon the work of others, consistent with the rules of copyright.

Amber Hawk Swanson is Officer, NYFA Source and an interdisciplinary artist.