Business of Art | What Writers Should Know about MFA Degrees, Teaching, and Carving Out Time for Their Work

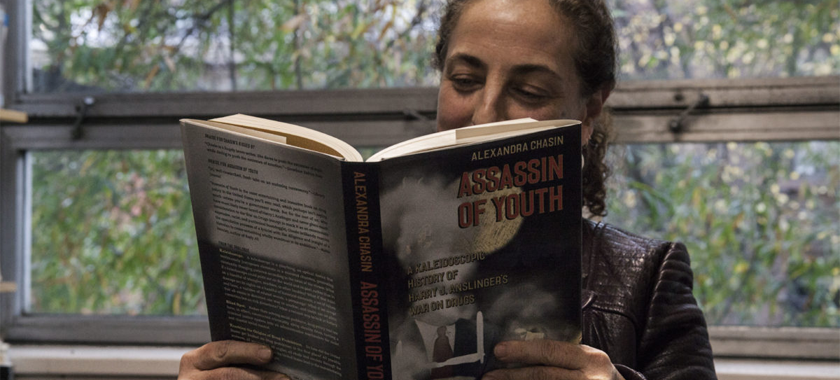

Insights for Writers from NYFA Board Member Alexandra Chasin.

Alexandra Chasin is the author of two books of fiction and two books of nonfiction, including Assassin of Youth: A Kaleidoscopic History of Harry J. Anslinger’s War on Drugs (University of Chicago Press, 2016) and Selling Out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). An Associate Professor of Literary Studies at Lang College, The New School, Chasin was the Founder and Artistic Director of Writing On It All, a public participatory writing project that ran for five years, from 2013-2017, on Governors Island in New York City (which was fiscally sponsored by NYFA). Her first performance work, Fragments, Lists & Lacunae, was produced at New York Live Arts in February 2020. Chasin is currently developing an ensemble performance piece that dramatizes the exclusionary effects, and the social, environmental, and spiritual costs, of the idea of “Man.” The moral of the story is the title of the work: UnMan.

Chasin received a NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship in Fiction in 2012. Other major awards include fellowships from the Whiting Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute, the Leon Levy Center for Biography at CUNY, and the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Chasin, who joined NYFA’s Board of Trustees in 2020, recently spoke with NYFA about her creative career and working in academia. Read on for tips about how she approaches both, and how they can work together.

The Promises and Perils of an MFA Degree

“There are promises and perils associated with an MFA degree in creative writing,” says Chasin. “MFA programs can be productive and stimulating, and the degree can have a certain professional utility. But it’s important to understand the broader social and economic MFA space,” she advises. “The reality is that a large majority of people who earn an MFA degree do not become professional writers. And even for those that do, most will be unable to support themselves financially through their writing. This circumstance is the same for the vast majority of professional writers who do not have an MFA, and for artists in every medium.”

Those interested in MFA programs and the publishing world may also want to consider that MFA programs in the United States are white-dominated and the publishing industry is both white-dominated and male-dominated. Furthermore, Chasin points out that because most students pay for their MFA degrees, the programs tend to be socioeconomically unrepresentative. “And it’s not just about identity,” says Chasin. “Aesthetically, politically, pedagogically, every which way, creative writing programs tend to operate within a narrow band—so for writers who work outside of centrist aesthetic and political norms, or for those who don’t thrive on a workshop model, those programs can be problematic.”

On the plus side, studying for an MFA generally offers a student generative structure, consistent feedback for their writing, and sometimes some contact with faculty and other students that may be important on personal and/or professional fronts. The practical use of the degree lies in its value as a credential for teaching jobs. The MFA is considered a “terminal degree,” meaning that it is the most “advanced” degree awarded in the fields in which it is available (though, Chasin notes, there is a small number of PhD programs in Creative Writing).

The Teaching Track

Teaching writing in a college or university generally takes two forms: part-time (adjunct) and full-time. “Both forms afford work in a potentially congenial setting, meaning the people and institutional values are in concert with intellectual and creative processes,” says Chasin. Teaching can be enlivening, and when an instructor is open to learning from and with their students, the work can support the expansion of the instructor’s creative and intellectual horizons. But part-time work is competitive—often an MFA degree is not sufficient and a record of published work is required. Part-time work is also time consuming and underpaid. But full-time work—this means a tenured or, more likely, tenure-track job in an academic institution—is even more competitive, and usually requires that much more of a publication record, on top of a terminal degree. Full-time teaching jobs come with a raft of perks, including research funds, and all kinds of access. Even so, writing, or creative practice, is one-third of the job, the other two-thirds being teaching and service; a tenure-track Assistant Professor is evaluated regularly, and ultimately faces a tenure process. “In other words,” says Chasin, “teaching full time is a career, a whole life.”

On Making Time for Your Creative Practice

“For writers who teach—as well as for writers who don’t teach—in addition to artists working in other media: creative work takes time,” states Chasin. “Everything in the world threatens to chip away at that time,” she adds. Better-paid work, searching for work, children and elders who need care, everyday administration of life, health issues, even sleep—the list of other uses of time is endless. For many nonartists, artistic work seems flexible, if it’s not invisible; it is hard for nonartists to credit creative work as real labor, especially if it is done in a residential space.

Chasin finds that all artists have their own idiosyncratic processes. “Because of my own idiosyncratic process, I find that I need 8 hours to do 4 hours worth of work. I also need to commit some of that time to the non-creative aspects of being an artist—submitting my work for publication or production, applying for grants, residencies, fellowships,” she says. As such, she encourages artists to “Submit, submit, submit. Apply, apply, apply.” Think of what a grant might enable you to do if you receive it: like teach one less course a semester to dedicate time to your art. All of this is to say that carving out time for applications can be valuable.

Says Chasin in closing: “I have learned, through trial and lots of error, to protect my time, in principle and in practice. I consider it an incredible privilege to do work that is meaningful to me—work that engages my core purposes as a human.”

–Amy Aronoff, Senior Communications Officer

You can find more articles on arts career topics by visiting the Business of Art section of NYFA’s website. Sign up for NYFA News and receive artist resources and upcoming events straight to your inbox.