Conversations | Celebrating NYC’s Immigrant Heritage Week with Shelley V. Worrell and Nicole Dennis-Benn

“I love going down dark avenues with my characters and allowing them to teach me more about humanity.” — Nicole Dennis-Benn

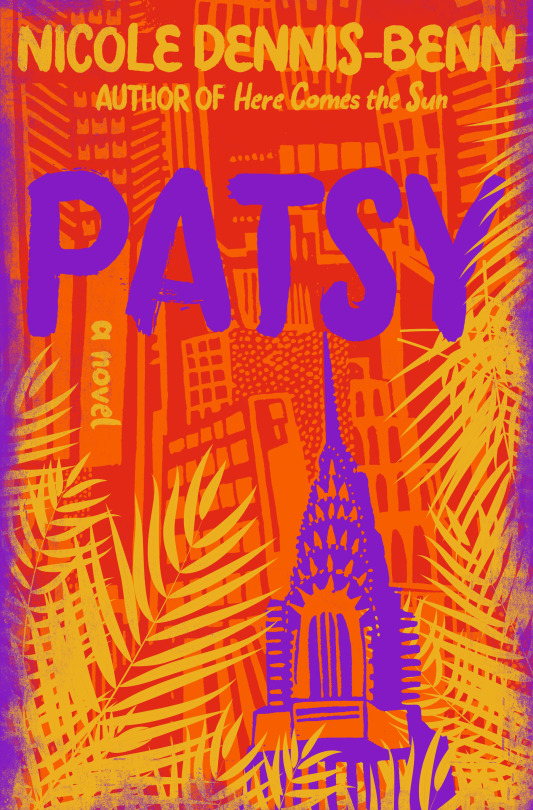

Shelley V. Worrell, Founder and Chief Curator of caribBEING (Fiscally Sponsored), joins NYFA Current to share her conversation with author Nicole Dennis-Benn (Fellow in Fiction ’18) in honor of NYC’s Immigrant Heritage Week. They discuss Dennis-Benn’s soon-to-be-released novel Patsy (Liveright, 2019), life as an immigrant in the United States, and the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. CaribBEING is a creative hub that builds cultural awareness and fosters Caribbean heritage through film, art, and culture.

Shelley V. Worrell: Your forthcoming book, Patsy, is set in Brooklyn, more specifically Flatbush, a neighborhood with one of the largest and most diverse Caribbean populations outside of the Caribbean itself. Why Brooklyn? Why Flatbush?

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Flatbush Avenue is a place I know very well and used as a canvas. I really wanted to capture the essence of the Caribbean immigrant community in Patsy. As a Caribbean immigrant myself from Jamaica, I’m always on Flatbush since the neighborhood reminds me so much of home—the smells, the sounds, the people. While writing Patsy, I found inspiration being around other immigrants and imagining their lives in the United States and back home. Most times I see them and interact with them on the surface level; but I also understand that freedom comes with a price, a loss of something—culture, memory, loved ones, a whole country.

SVW: Being a new immigrant is often an isolating experience. Can you tell us about your immigrant story? Have you seen “foreign” change since your arrival, for the better or worse?

NDB: Yes, being a new immigrant is extremely lonely! I wrote about my experience, which was recently published in BuzzFeed—an excerpt from the Good Immigrant USA anthology (Little, Brown and Company; 2019). And that’s only half of it! Like most immigrants, America was sold to me as a fantasy. But I quickly realized that it has issues like anywhere else. The most shocking realization was being more aware of my blackness. It’s one thing to be a working-class dark-skinned black girl in Jamaica, but it’s another thing to be a black woman in America. Here, black is black is black. I also realized that I’m just as restricted in this black female body in America as I would have been in Jamaica, especially as a lesbian.

SVW: “Back home” has a strong influence on your writing. From patois to aesthetics (fashion), has that evolved since migrating to the U.S. and more specifically to Brooklyn?

NDB: A former college professor once told me that “You never truly left home. Home is here with you in your memories, which like the imagination, only belongs to you.” I will never forget that. I’ve since realized that she was right. “Home” will always be with me. In terms of language, I never lost that either. In fact, I fight harder to reclaim Jamaican patois in my work, given that we were discouraged from speaking it back home. Patois is our first language, yet we are conditioned to speak standard English in schools. I always thought it was unfair to tell people not to speak their language. That’s an erasure of identity. As an artist, I want to preserve our language on the page. Even if I don’t speak it as much in my new country, I still dream and create in it.

SVW: I also appreciate the integration of a Queer-identified subject in your work. Can you give us some insight on your creative process and how it ties to your sexual identity?

NDB: Patsy’s story came to me as a confession—a relentless stream of consciousness of a woman, a mother, who deliberately seeks to reinvent herself in America and revel in the freedom it offers her to love the way she wants to love. Hers is a story I wanted to explore—a story that goes against everything we thought the immigrant story to be: altruistic. It’s easy to see now that Patsy’s story is my own in that I, too, chose America to redefine myself. I had always felt like an outsider as a lesbian woman in Jamaica, where homosexuality is taboo and opportunities for the working-class are limited. I wanted to simply be, to find a home in myself elsewhere.

SVW: In Patsy, you talk about barrels and I couldn’t help but think about its connection to Caribbean immigration and to the Diaspora. Why barrels? What are their significance to Caribbean communities both here and back home?

NDB: Barrels are a staple in any Caribbean immigrant community since they are large enough for individuals living here in America to send a number of things back home to family. Not many immigrants are able to go home as often, or at all, to see the family they left behind. So, barrels become an essential way to send gifts and food and other necessities in their place. In Jamaica, the children who depend on parents who live abroad are referred to as “barrel children.” It’s really a class thing. While some households—middle-class and upper middle-class—can afford to have both parents living and working in Jamaica, others who are mostly working class can only keep afloat financially when one parent, or both, finds work overseas in countries like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, where the dollar amount is worth more than Jamaican dollars. This is how many of us could afford to survive. Many people who leave the island for better opportunities and a way to help their families are often criticized for leaving despite there being no systematic changes in place to keep them home. The government—upon realizing that remittance is the biggest revenue for Jamaica next to tourism—choose to capitalize off immigration. Hence, those barrels and money transfers from the Jamaican diaspora living abroad, is what’s making the Jamaican economy thrive. But what remains is stigma. There is the side-eye given to parents who send barrels in their place; and the hush, encapsulating grudge and pity, which follows the recipients.

SVW: It seems like immigrants are under warfare in the U.S. Are there any references to the current climate in your work?

NDB: Patsy is set between 1998 and 2008. What Americans don’t realize is that the American government has never been kind to undocumented immigrants like Patsy. Every administration on both sides have deported a significant number of undocumented immigrants despite their ties to family in America. The difference with the current administration is that they’re more vocal about it.

SVW: What do you want people to feel/take away from Patsy?

NDB: For Patsy, I found myself having to get rid of my own judgments of a woman who not only lacks the desire and capacity to mother, but who abandons her young daughter. I had to unlearn my own expectations of what a mother is expected to be; and more specifically, who we are expected to be and what we are expected to desire as women. Having those personal conflicts is what I love the most about the writing process. I love going down dark avenues with my characters and allow them to teach me more about humanity. I hope my readers will walk away with the same enlightenment, transcending their own understanding of the world to empathize with a woman who is seeking to find her place in a world already set on defining her.

SVW: You’ve had a long history with NYFA, having received the NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship. How has that impacted your career?

NDB: I was really grateful for the generous NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship. I was able to pay my bills, which is really important for an artist. It gave me more mental space to focus on my work as opposed to stressing too much about livelihood or quality of life.

SVW: Is there anything else you would like to add or we should look forward to?

NDB: Well, I’m certainly looking forward to the launch of Patsy on Tuesday, June 4, at Greenlight Bookstore—the Flatbush Avenue location with U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith. How fitting it would be to celebrate the book in the very place where it is set!

— Interview conducted by Shelley V. Worrell, Founder & Chief Curator of caribBEING, a NYFA Fiscally Sponsored organization.

Images: Courtesy of Nicole Dennis-Benn

Are you an artist or a new organization interested in expanding your fundraising capacity through NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship? We accept out-of-cycle reviews year-round. No-fee applications are accepted on a quarterly basis, and our next deadline is June 30. Click here to learn more about the program and to apply. Sign up for our free bi-weekly newsletter, NYFA News, for the latest updates and news about Sponsored Projects and Emerging Organizations.