Conversations | Helène Aylon & Feminism: A Fiscally Sponsored Artist at the 2017 Jerusalem Biennale

“Art history has been one incomplete truth, which makes it a lie.”

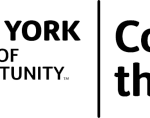

As the conclusion to a 20-year NYFA Fiscally Sponsored project, “G-d Project: Nine Houses Without Women,” Helène Aylon’s exhibition, Afterword: For the Children is now on view at the 2017 Jerusalem Biennale. Aylon is a prominent American visual artist and feminist and her exhibition forcefully confronts the Second Commandment (specifically “I Thy God, will visit the sins of the fathers onto the children—to the third or fourth generation of those who hate me”) as if to reclaim children and their future from an underlying and sustained patriarchy within Jewish texts.

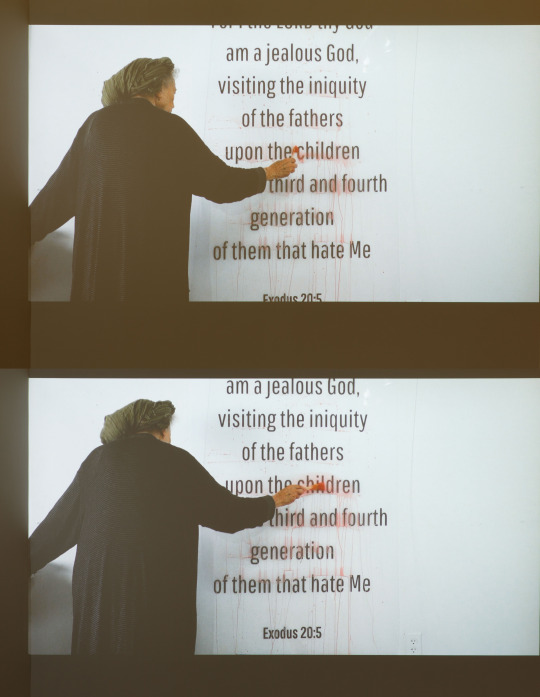

Under the title of Watershed, this year’s Biennale presents works that add to the conversation of Contemporary Jewish Art and signify both the splits and convergences between individuals and groups. Aylon’s work not only literally extends the Watershed metaphor as they reflect tears of the children but also suggests the partitions and inequalities that exist in our society today.

Along with fresh insights on Aylon’s participation in this year’s Jerusalem Biennale, we are delighted to re-share an interview with Aylon back in early 2016, where we celebrated her achievements in the art world for Women’s History Month.

Title: Helène Aylon’s exhibition Afterword: For the Children at the 2017 Jerusalem Biennale

Exhibition Dates: Now through November 15, 2017

Hours: Sunday – Thursday, 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM

Where: Hamachtarot Museum (Museum of Underground Prisoners), Rehov Mishol Hagvura 1, Russian Compound, Jerusalem, 9131401

NYFA: Central to the Jerusalem Biennale is the question of whether there is such a genre or concept of “contemporary Jewish art.” Do you consider your own work in that category?

Helène Aylon: I do not consider my own work “contemporary Jewish art.” My work merely looks to “rescue” myself from patriarchy wherever it comes close to me. In the 70s, with my process paintings, “The Breakings,” I challenged the playboy culture with images of the body as visceral—because the body leaks and sweats and shrivels and gives birth, etc. It makes one live or die. In the 80s, I sought to face the Arms Race which was also cowboy-esque with its male rivalry acting out which faction had the bigger stockpile of arms. This sickness inspired the Earth Ambulance. In the 90’s, I had to look at my own orthodox Jewish upbringing and schooling, and I sought to liberate G-d from the projection of my patriarchal forefathers who also dismissed the precious history of my foremothers.

Now, in my current appendage to my 20-year “The G-d Project: Nine Houses Without Women,“ my addendum currently at the Jerusalem Biennale is called Afterword: For the Children. I am distraught that the Second Commandment of The Ten Commandments states, “I Thy God, will visit the sins of the fathers onto the children—to the third or fourth generation of those who hate me.”

Therefore, as it were, I am “rescuing” G-d from the patriarchy!

NYFA: Your work engages with and at times poses as opposites themes of Jewish orthodoxy and feminism. Is there a relationship between these two themes? Are they opposites?

HA: I am being a detective, so to speak—searching for the anonymous prayers and traditions that have no authorship—and imagining that these were written and inspired and made into a female tradition by the foremothers. For example, lighting the Sabbath candles is not prescribed in “The Five Books of Moses.”

NYFA: Since beginning your career in 1960’s New York, you witnessed transformations to the art scene, the fabric of the city and cultural perceptions of feminism. How have such social and cultural changes influenced your studio practice? What do you think the landscape for emerging artists is today, in comparison to when you began exhibiting work?

HA: Emerging women artists have more opportunity to be seen and hopefully will change the culture if they see the legacy bestowed upon them with appreciation.

The greatest nonviolent revolution has been feminism. I am focusing on the tragedy of lost foremothers we will never know and what their great contributions might have been. I see myself as a future foremother. Art history has been one incomplete truth, which makes it a lie.

NYFA: In a June 2017 article titled “Why Old Women Have Replaced Young Men as the Art World’s Darlings,” there is talk about the growing, commercial interest of older women in the art world. Do you think this is evidence of gender equity and a success of feminism?

HA: Yes, this is delayed consciousness raising! It has taken a long long time to catch on, but once it goes click, the obvious reality cannot be overlooked.

NYFA: You began taking courses at Brooklyn College when your daughter entered kindergarten. What fueled your decision to study art and how did your mother and father respond?

HA: My mother would rave about the birthday cards and Jewish New Year cards I designed for her and would introduce me as her “daughter the artist” to distinguish me from my two younger sisters. I knew that my mother surely had a different concept of art. Perhaps she thought it might even be a plus when I came of marriageable age! But her designation, no matter the derivation, was encouragement enough for me.

I yearned to express myself and live my life on my terms. Before, I did what my parents dictated, what my teachers dictated, what my late husband dictated, what the community dictated and thus [this is] what my children came to expect. Art would be something they could not dictate.

I played down my secret thrill of attending Brooklyn College as an art student, though I felt much older than the other students. In this way my father could rationalize that I was getting a college degree so I could teach art and get a job.

NYFA: How did you support your children and negotiate the demands of motherhood with your work as an artist?

HA: Always my children came first and my art came next, but the art would not be compromised.

I tried a NY Times ad: working at an ad agency. I soon got fired. I tried to get a job as a guard in the Metropolitan Museum but they saw right through me. I applied for grants. I got into one of the first SoHo galleries, Max Hutchinson Gallery. Then, before my exodus to California, I signed up with Betty Parsons Gallery.

I taught for a few years in San Francisco State University which was my excuse for getting far away. I would sublet my studio when in San Francisco and also when I went to retreats such as Yaddo, Macdowell, VCCA, to avoid paying rent and still have a place to make art.

My uncle thought I should design wallpaper, my late husband’s teacher thought I could fake an accent and get a job advertising on TV. I would feign interest but ignore these “practical” suggestions [and] continue to struggle.

After my job was over and I did not get tenure at San Francisco State (see my memoir for why!), I no longer could afford the studio where I created the liquid sacks that broke. Nuclear America became my studio when I drove the Earth Ambulance to ‘rescue’ the earth from nuclear military sites in pillowcase sacks.

It was never smooth sailing and the situation has barely improved, even now, after getting a Lifetime Achievement Award on my 85th birthday last month. My small studio has become a storage space. I am now able to create art around activist work, but I have not a clue how to find a gallery. Betty Parsons found me and so did Max Hutchinson and Susan Caldwell. What gallerist will find me now?????

NYFA: The obstacles you faced and are currently battling seem to resonate with other artists. Where do you find the motivation to sustain your practice?

HA: I am motivated to learn for myself in ways that only art can teach.

NYFA: What artists inspired your work when you were beginning to make art and what artists are you looking at now?

HA: Then, my teacher at Brooklyn College was Ad Reinhardt, who did not teach but made me think. There is no “how to” and each artist must find the answers in oneself or ask the questions to oneself. But what gets me going is where I left off in my own last piece.

Now I like to look at Agnes Martin who said that “helplessness is the natural state for an artist and this is a good thing.” I relate to Ana Mendieta and dedicated my installation Wrestlers to her. I am drawn to Mierle Ukeles (who in the early ‘80s jokingly called herself and me “Mitzva Artists”), William Kentridge, Martha Rosler, Maya Linn, Bill Viola, and then there is Glenn Ligon… In 1996 Glenn Ligon wrote to me that he liked my "austerity” in The Liberation of G-d. But I am so blown away by his emotional splotches in his work. I wish I did not have to contain myself politely when it comes to my emotions about the misogyny and the erasure of the female. But I must “austerely” allow the viewer to be the Midrashist as the text I use is scripture, which is supposedly the words of G-d…

NYFA: “The G-D Project” has been fiscally sponsored since 1999. The work explores the way God has been used in the Old Testament to reflect patriarchal characteristics. Why did you initially seek sponsorship and how has sponsorship made this project possible? How did “The G-D Project” evolve over the past seventeen years?

HA: It was hard to deal with this very personal subject matter. G-d can be a potentially inflammable volatile subject. Calling it a “project” through NYFA neutralized it so that it could be looked at as an artwork. Furthermore, seeing G-d through a feminist lens became tagged as theological which made it easier to absorb. These subtle factors took away any sermonic stance that brings out tensions. Working through NYFA thus set the tone for exploration and radical truth-telling which is the realm of artists.

“The G-d Project” used my background to deal with feminist issues such as inequality. I find that theological feminism has not yet been dealt with, as has biological feminism and ecological feminism. The San Francisco Jewish Museum programmed “Four Rabbis and an Artist: A Talmudic Debate!” Yes, I took on Orthodox, Conservative, Reformed, and Reconstructionist rabbis! The National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and Ackland Art Museum all programmed this debate with Rabbis from their communities. The Liberation of G-d and the Unmentionable has been the subject of a conference and the thesis of a Ph.D. and [these] theological public debates were viewed as activist performance art.

In Jerusalem women judges are forbidden to judge in the religious Court, which is the subject of All Rise. A patron has offered to pay for its transportation to Jerusalem if it will be shown in the Jerusalem Biennale in 2017. I am holding my breath as this has the potential to affect change.

-Interview by Madeleine Cutrona, Program Officer, Fiscal Sponsorship; Updated and edited by Priscilla Son, Program Assistant, Fiscal Sponsorship & Finance

NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship’s next quarterly no-fee application deadline is December 31, and you can learn more about NYFA’s Fiscal Sponsorship program here.

Images from top: Wipe detail, Photo Credit: Susan Sandholland; Vanishing Pink Children, Photo Credit: Heratch Ekmekjian; Tears for the Children, Photo Credit: Jacob Kleinberg; Tears for the Children detail, Photo Credit: Heratch Ekmekjian; Wipe detail, Photo Credit: Heratch Ekmekjian