The Business of Art: A Conversation with Jenny Dubnau

Jenny Dubnau sees the act of portrait-painting as making fictions of sorts, though she seeks to get as close to the truth as she can in her unflinchingly realist work.

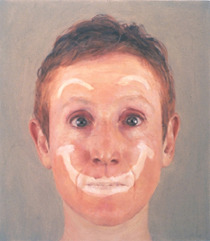

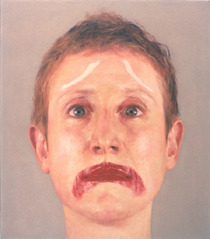

She’s been called “brave” for paintings that she’s made, particularly her meticulous renderings of her own facial “flaws”; moles, nose shine, and blood-shot, tired eyes. Dubnau’s work is emotionally charged, capturing such complex emotions as fear, surprise, and shame, and straddle these emotional archetypes of human vulnerability while offering something specific about the sitter in a moment of time. Her compositions are simple, or perhaps a better word for them is direct, akin to a mug shot format. She paints friends and family; those that she is intimate with—not from life, but from photographs.

I photograph the subjects in my studio. I sit them down in a chair, and shine some pretty strong, glaring lights on them. I need to use that much light so the photos contain enough detail for the paintings, but I also think there’s a vulnerability about having such strong lights on you: it feels almost like an interrogation. (I know this from photographing myself.)

When Dubnau asked me to sit for her a few months ago, I agreed, despite my initial discomfort in how I might be portrayed. I visited her studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, where she’s been making paintings for the last ten years. She placed a chair in the middle of the room and directed me to sit down while she set up lights and her camera on a tripod. I looked straight ahead, either at the camera or else at the paintings of her mother, father, and friends on the opposite wall, which seemed to hover as if suspended over us. I heard the shutter click. Dubnau then lifted the lights and carried them closer to me. I felt the growing heat coming off the bulbs; the lights’ convex interior, covered with a metallic foil material, drew my eyes to them, though the brightness hurt if I looked too long. Dubnau asked me if I wouldn’t mind pulling my hair away from my neck and face, and then brought the lights and the camera even closer. And that’s when she began to get photos that she liked. All in all, the process took no more than twenty minutes.

We all know that the camera will capture us “as we really appear,” so vanity makes us tense up and put on a protective mask. I’m interested in both showing that mask and piercing through it.

“This is the one that I like best,” Dubnau said, and showed it to me on the screen of her digital camera. Something about the photo made me look like a newscaster. And yet because my mouth was parted, exposing my front teeth (which thankfully looked white enough to me), and my head was cocked to one side, I also seemed slightly dim-witted. My eye shadow and lipstick had vanished in the brightness of the lights. There were other pictures, too, and I bit my tongue, not saying that I preferred any over the dim-witted one. Because it wasn’t about me anymore. And it wasn’t really me per se, in that photo, in that moment, it was just a flicker of something—the newscaster quality, the dim-wittedness, the teeth, the stark white skin—which Dubnau had frozen in time.

When I get the images home and edit them on the computer, I look for an interesting color dynamic, a revealing light cast over the subject, and most importantly, an enigmatic, charged facial expression and body language. When I make the paintings (which of course is the most important part), I allow the process of painting to intervene into the photograph as object, meaning that the language of making space and creating metaphor through paint is the goal, rather than simply “copying” the information in the photo. I do allow photographic references to remain in the paintings, though, because being subjected to the eye of the camera is so important to the content of my work.

What follows below is a back and forth between Dubnau and me, which occurred just before sitting for the photographs that she took of me.

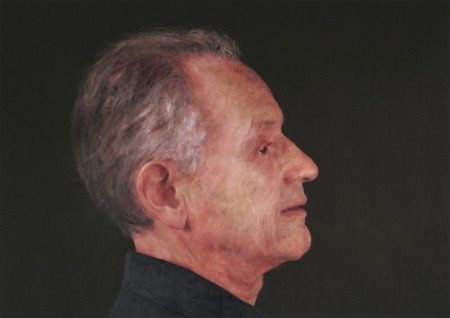

Jenny Dubnau: I’m always thinking about how people feel about being revealed in my paintings. Because to say that my work is not about stroking people’s egos is an understatement. The paintings are about showing everything in someone’s face, and really focusing in on the imperfections, the little quirks and signs of aging. That’s so much a part of it. I find those vulnerabilities really beautiful

Suzan Sherman: Yeah, I do too, particularly in these paintings (pointing to the wall) of your dad and mom.

JD: But how would you feel—aside from how you feel about these paintings of other people—if I painted you, and there was something about the lighting or the way that I rendered something in your face that you were most insecure about, how would you feel?

I have some friends who won’t sit for me. Because they know what I do. But for whatever reason, I don’t care when I paint myself. I’m able to split off from the part of me that functions in the world and goes to work and wants to look pretty. We all have vanity, but when I’m in the studio I’m able to disassociate.

SS: Your face becomes your workplace.

JD: Right. [laughter] It’s what I do. But I do appreciate and understand that even if some people agree to pose, they might, in the worst-case scenario, end up being hurt by what I end up making.

SS: Has that ever happened?

JD: Yeah. It’s happened more than once. There was one situation in particular in which some people were deeply upset about how they looked. Upset to be seen in public in the way that I pictured them. And it was deeply upsetting for me.

SS: Why was it upsetting?

JD: To be honest, I didn’t think that the paintings made them look bad, and it shook me because it made me think, maybe I’m just not seeing correctly. It made me wonder, are these repulsive to other people? Because I have no desire to make a repulsive image.

SS: I don’t think they’re repulsive, but you know that “mirror face” that people put on? There’s that particular way they want to see themselves in their reflection, the way that they relax their muscles or set their mouth and eyes in a very specific, narrowly confined way.

JD: Yes, right.

SS: But you’re capturing a gesture, a flicker of feeling, like your painting, Denise crying. It’s not meant to be the total embodiment of a person.

JD: I’m also a realist painter, so to a great degree it’s very much about resemblance. Not as much as with a photograph, but I paint all the flaws and imperfections that are there. On the other hand, a lot of what goes into these paintings is my projection and have nothing to do with that other person. And that’s what’s really hard to tease apart, capturing something that’s really real about a person versus my own projections. The way these paintings look is very realistic, that’s their style, and they come out of the Realist tradition. Not just of being representational, but of being realist in the sense that they’re not particularly idealized, they’re not particularly generalized, they’re not dreamlike or surreal. Their style is direct observation and showing “what’s there.”

But even though that’s their style, it’s really all just projection and fakery, because it’s painting. It’s a trick. In a way it shocks me when someone looks at a painting I’ve done, of someone they know, and they say, “Oh you really captured their fragility.” I always feel like, did I? It’s all so subjective and mediated. It was a snap of a shutter when I took the photo. Someone could end up looking like a mobster, or cruel, or sweet, or insecure, depending on the moment.

A subject is mediated by the photographic process, and then there’s a whole other layer of mediation by my own projection of how I see the person. And then there’s a whole other layer of projection because the photograph and my interpretation of that photograph are being put through this unbelievable filter of painting, which is even more removed from reality. So how does any original aspect of a real person survive all those layers? It would probably be a lie to pretend that nothing remains. There’s probably a little nugget of something that relates to the person, but it’s so enigmatic to get to it.

SS: Do you hope, ideally, for that nugget to remain in the finished painting? Or in the end is it not that important to have an aspect of the real person still there?

JD: That’s an interesting question. Because if you ask me, do I want these paintings to look like the real person, I would say yes, absolutely, that’s super important to me. And I always wonder why I care about that so much. A lot of times when I’m making them, I’ll look at the painting and I just know that my work is at its strongest when it’s most realist, when it’s more and more “accurate” to what the person really looks like.

I know that that’s true. I’ll keep correcting and correcting and correcting because, even if it kind of looks good, I’ll think that I want the nose to feel even more like X’s nose. I think it has to do with an almost philosophical stance of being a realist, where the metaphor becomes most active when you’re hewing more closely to what really is. It doesn’t mean it really is what is, it just means that it’s appearing to look like what is, if that makes sense.

But what I don’t have an answer for is the question of capturing an aspect of the person’s character. It’s so enigmatic that I don’t know if it’s important to me or not. I know what I might think of that person. I know what my feelings might be toward that person, but I feel it’s so super-duper filtered through the processes of making the painting that I don’t know if I could identify if it were or weren’t there. It’s so far away.

On the other hand, there are times when I look at one of my paintings of someone that I know well and I think, I really captured so and so’s attribute. But then I mistrust myself right away and think that I might have captured it, but that it’s my own individual take. I don’t know if that comes through universally. Then it gets down to how we see people, and everyone responds differently. One person will look at a face and think, “Oh that person looks angry underneath,” and another person will think, “No they don’t.”

I’ve done a lot of images of people smiling or laughing or making funny faces and I’ve moved away from that. Partly because I think it’s so much more interesting to have a relatively neutral expression that becomes a screen for projection, upon which we can imagine reading a myriad of feelings and psychological attributes. I like it to be enigmatic—and I don’t mean vague, I’m not trying to duck the question—but I want it to arise in the painting as a question in someone’s mind. What is this person thinking or feeling? And the more relatively neutral their expression is in a nameable kind of way, the more we can read little flickers of all different kinds of emotions and thoughts.

SS: There’s something about your face that has always reminded me of Cindy Sherman; there’s a resemblance between the two of you. Like her, you have a certain type of face where it’s not that particular—you can push it in a lot of ways, and you both work with that aspect of yourselves, putting on different personas.

JD: Cindy Sherman has been a very important artist for me. When I was coming of age and forming my sense of self as an artist in the ’80s, she was crucial because of the content of her work. This kind of quicksilver notion of the self, especially in a gendered way, of women—not just how we’re pictured, but how we feel about ourselves. We’re constantly shifting into other people’s points of view when we think about ourselves.

That’s something I think about a lot, though not as much as I used to. A lot of my work has been directly influenced by Cindy Sherman. I put costumes on and played myself in different roles, wearing wigs and making funny faces, taking on an exaggerated persona of “an angry person,” say, or “a sad person.” Now I’m going back to feeling like painting a traditional portrait of a person is more than enough. I can put all the content that I want in there. My work used to be a lot more exaggerated and humorous than it’s seeming now.

That’s the other thing about having people pose for me. It’s the whole act of doing a photo shoot. In a way it’s literally a stage set that’s lit and completely fake. And the person is completely aware that they’re being photographed, and they’re putting on their “I’m being photographed” face, and they’re presenting themselves. And we’re agreeing to do this out-of-time, out-of-reality moment. I also have a hand in it by how they sit in front of the camera, how I light it, and which image I end up choosing. And I admit that I have more control than they do—much more. [laughter]

I stage direct to some degree. You’ll see—I say turn slightly to the left, look slightly up, can you open your mouth, part your lips slightly, can you roll your eyeballs up or to the left, very simple things. It’s completely fictional. Fictional is probably a better word for it than false.

I’ll be interested to hear what it feels like for you to sit for me, and especially afterward, when you see the finished painting. I always get a little anxious when I show people the work that I’ve done, that they’ll either be upset or act like they like it, but I can read in their voices that they’re unhappy or embarrassed, because it’s painful for them to see themselves portrayed in the way that I do. Ethically it’s hard because I never want to hurt anyone’s feelings or make anyone uncomfortable, ever. But at the same time, I really need to make these paintings.

SS: Have you ever painted someone you don’t know?

JD: Yes. I have. I’ve done a couple of commissions. Those are hard for me to do. I don’t know whether it’s because I don’t know them—I have a feeling that’s not it. With the commissions, the thing that’s hard is that they’re paying me to make an image of them, and I always feel like even if they say, “I don’t care about vanity, do whatever you want to do, I love how you make a painting,” I still end up feeling constrained. Which might be my problem. I never feel like I can quite make the painting that I would if that contract didn’t exist. I feel like I have to pull back just a little bit, or tamp down what I would ordinarily do to make them look good. It’s not as fun of an experience. The paintings seem less ambitious, less no holds barred. You know, when choosing a photo, when I edit the photos from the shoot with you tonight, I’m just going to pick the one that my gut just tells me I want to do.

Although again, I’m not interested in making grotesques. I always think the people in my paintings are very beautiful, even if the moment’s a little awkward, or if their hair is a little mussed, or there’s a little shine of oil on their nose, or they have a little zit on their chin or something. They might think, oh God, this is terrible, and I might think, don’t worry, you still look great.

But the thing about it is that I genuinely think you look great, I’m not just faking it. I mean to me everyone looks very beautiful in their human-ness. I do that to myself, too. With my own self-portraits, sometimes I really let myself go, more than I might allow myself to do with someone else.

SS: Didn’t someone once say, and you found out later, that “that Jenny Dubnau is brave”?

JD: Someone did say that while looking at one of my self-portraits. And the funny thing is, it almost brought me up short, because it made me think, oh my God, do I really look that terrible in that image? Because I had to assume what he was referring to was vanity, that I had no vanity, but of course I do, like any other person. But in the paintings I guess I don’t. At the same time, I didn’t think of myself as looking unattractive.

I have two moles on the side of my face and the light was shining on them, and I totally put them in. I painted all my little foibles, like the little creases on my neck. But in the process of making the painting it felt fine, but for some people all they can see is that I don’t look pretty. And I don’t know what to think of that.

A part of me wants to critique our society too, which is so intensely focused on how we look and on being young. And believe me, I’ve had some negative responses from the art world to even the idea of my painting old people. Which pisses me off. My parents are in their seventies, and to me they look fabulous. I guess the art world’s concern is that the market wouldn’t be interested in buying paintings of people who are old.

And my jaw wants to drop when I hear something like that—that our society can’t even behold images of people who are older. Are they that repulsive? What could be more interesting than looking at someone who’s older and what happens to our bodies? You get so much experience of the world in your eyes, and why is that a negative? Of course everyone is afraid of getting older. We’re all afraid of death.

SS: So as you get older, does it make it harder for you to paint yourself?

JD: No. If anything I want to paint myself more. It’s wonderful fodder for me to paint my aging face. And I will totally do it. I’ll just keep on painting the wrinkles and the age spots.

Because the paintings really are about mortality on a certain level. I think that’s in everyone’s faces that I paint. Or perhaps that’s something I’m projecting onto them because it’s something I think about a lot. Painting and aging.

Lately I’ve been trying to paint infants and babies, and I just haven’t found a way in yet. Part of it might be because it’s hard to push past the sentimentality of the baby, but then another part of me thinks that it’s just not the right subject for me. Because they’re so beautiful and flawless. Maybe I have to paint people who know that they’re mortal. We all have this knowledge that we last as long as our bodies do. And babies have no idea. Their conflicts consist of being cold, hungry, bored, or tired, and for me at least, that’s not particularly interesting, psychologically.

Jenny Dubnau paints photo-based psychological portraits. She grew up in New York City, and received her MFA from Yale in 1996. She has shown at P.P.O.W. and Black & White Gallery in New York, Clifford-Smith Gallery in Boston, and Bernice Steinbaum Gallery in Miami. She has a show up currently at Bucheon Gallery in San Francisco. She is the recipient of a Tiffany Foundation Grant (2001), a Pollock-Krasner Grant (2004), a Guggenheim Fellowship (2004), and a NYFA Fellowship in Painting (2008). Dubnau lives in Queens and paints in Brooklyn.