The Business of Art: A Conversation with Poster Boy

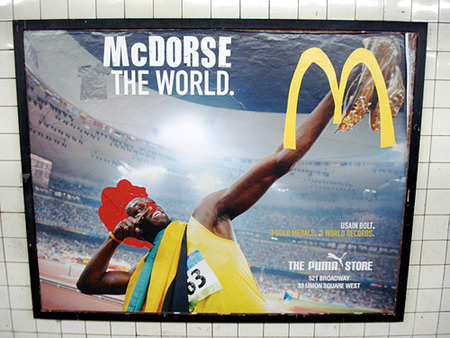

Suzan Sherman: An aspect of your work that I especially appreciate is that you’re not applying anything new to the subway ads that you work with, such as paint or Magic marker. Except for your razor blade, you use what’s there. But because of this your mashups can at first be deceiving. One can do a double-take and wonder, Is that an ad? Through combining two or more images from advertisements in such surprising ways, you’re proving that the visual culture of advertising is oftentimes both blatant and sneakily subconscious.

Poster Boy: Sometimes entire compositions are appropriated, and when this happens my piece is as effective as the original ads in “catching the eye.” Other times very recognizable signs (logos, celebrity faces, etc.) and slogans are juxtaposed. In both instances the power of the original image is retained. Sometimes I worry that I might be helping the advertisers. However, what I want is for people to know that it’s possible to change their environment.

SS: You’ve been doing these subway mashups since January. Before this, had you done any work that manipulates the environment?

PB: No prior experience. I don’t have the money to constantly buy materials, nor do I have the space to create or show art. I’m also tired of the saturation of ads, political process, economic system, and all other aspects of our capitalist system. The end result is an angry and disenfranchised artist.

SS: How often do you work? Bring me through the process of making one of your mashups.

PB: In the beginning I only did them on the way to work, school, or home. Since gaining some notoriety I’ve been taking a little more time out of my day to create these pieces. When I get off work, I skim through all the ads on the platform. After making a mental note of what I have to work with I allow my mind to make all sorts of connections. The pieces are conceived in my head at first. The possibilities are large when all things are considered: color, text, images. Usually I’ll find a main/base poster. Then I’ll introduce content from other posters in order to finish the piece. The process doesn’t take too long once I know what I want. However, I have to create under pressure due to the MTA and NYPD.

SS: In a profile that featured you in the October 5 issue of New York magazine, writer Brian Rafferty went down to the subway while you worked. It was a Thursday evening and commuters were there, waiting on the busy 23rd Street C/E station platform. In the midst of it, some cops stopped you, took away your razor blade, but let you go without arrest. I had assumed you worked in the middle of the night—aren’t you at all concerned about getting arrested?

PB: I worry about getting arrested only because it would tie me up in the “system.” However, I’m not afraid of confrontation. I’m ready to fight for what I feel is right as opposed to what is legal. And no, it wasn’t in the middle of the night. It was just after rush hour. I should add that Brian conveniently left out a juicy morsel from his profile on me. I told him that the only way I’d let him follow me into the subway is by doing a piece himself. I’m not mad that he left it out of the story. I’m just glad that he paid the fee to get the scoop.

SS: There’s a quote from you in that profile that says: “No matter what I do to the piece, as long as I did something to those advertisements and that saturation, it’s political. It’s anti-media, anti-established art world.” I’m wondering who, by definition, is established, and do you consider the media and art world synonymous?

PB: There’s no clear-cut way of identifying the media or established art world. Like all labels, they exist on scales. I could claim anti this and that, but as long as I’m addressing these institutions Poster Boy will always exist on the same scale. However, Poster Boy exists on the far end of the media/established art world spectrum. I’d say Murakami and Hirst are on the other end of that spectrum. I don’t mind this at all because Poster Boy traverses many spectrums: media, advertising, vandalism, street art, graffiti, art, etc. What I probably should’ve said is that Poster Boy is more anti-media and anti-established art world than most.

SS: Why did you drop out of art school?

PB: I had one credit left my senior year. I just wanted to prove, to myself and others, that one can be “successful” without the approval of an institution.

SS: Who are your heroes?

PB: Noam Chomsky, Mos Def, Immortal Technique, Frederick Douglass, Rimbaud, Amy Goodman, Mike Tyson, George Orwell, Andy Kaufman. There’s a couple of others that I can’t think of right now.

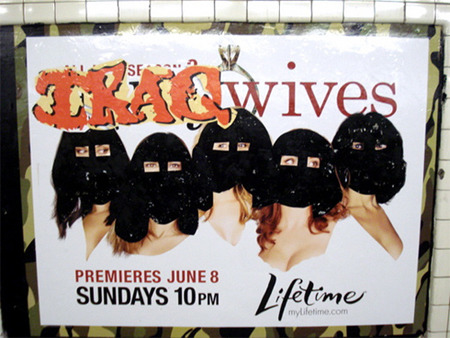

Poster Boy

Iraq Wives (June 2008)

SS: Besides the people who might come across your work on a subway platform, you’ve also set up a Flickr account (www.flickr.com/photos/26296445@N05) so the public can access the work that you’ve done in the past. Do you consider this accessibility of your work on Flickr, by people interested in viewing it, as decontextualizing it in some way, and therefore not as primary of an experience as a random subway rider seeing your work by chance and involuntarily feeling affected by it?

PB: No, it’s just different. The Flickr stuff exists for people who don’t ride the train or who don’t know what the original ad looks like. The physical pieces are personal to NYC commuters. It’s a little like what happened when graffiti entered the gallery scene. The subway pieces are more intimate, but the online pieces are more accessible. One isn’t better than the other, just different.

SS: Your work is spontaneous, completed within minutes, and then seen online by who knows how many viewers without a big-budget supporter or an exhibition space. It’s freeing, I imagine, to toss away the need for backing and just do what you want. But is the temporariness of the work ever frustrating to you?

PB: The ephemerality issue is no different than the labeling issue. It functions on a scale. All things have a life span. The temporality of my work limits the amount of people who experience the physical pieces, but it also keeps people from owning anything either.