The Business of Art: A Conversation with Shaun Leonardo

Combining the costuming and symbolism of Lucha Libre (Latin American professional wrestling) with the physicality and athleticism of American pro wrestling, Shaun Leonardo (aka El Conquistador, or just El C.)’s performances notoriously rouse stoic art audiences to cheer and squeal like they’re at a sporting event. And they are, in a sense.

Since 2004, Leonardo has battled and bloodied himself in meticulously staged wrestling matches against an invisible opponent, observing a strict pre-fight training regimen in order to sculpt his body into appropriate physical shape. The matches against The Invisible Man, according to Leonardo, are “not only a physical battle against societal obscurity but also an internal struggle with the vulnerabilities of [my] own identity.”

His final performance before retiring El C., the character he created to combat The Invisible Man, will take at Corona Plaza, Queens on September 15 as part of a Queens Museum of Art public art project. After blanketing Corona Plaza with promotional posters for September’s performance, curator Herb Tam spoke with Leonardo about masculinity, identity politics, and liability insurance.

Herb Tam: I want to start out by talking about risk in your work. You’ve been caught in the liability insurance web before because of the extreme nature of your performances. Given that this is a common obstacle for you, can this be interpreted as an embedded form of institutional critique?

Shaun Leonardo: There’s a very real part to the whole process of putting on a performance where it takes the form of a contract with the space. The whole relationship is based on trust. The inherent critique of the institution is that the performance puts them in a position where they need to put away their own ego and apprehension towards performance work in general in order to believe in my piece and in me as an artist. I’ve become increasingly conscious of the fact that I can only pair myself with institutions that are not only going to believe in the risk factor, but in the severity that goes into creating my kind of work.

HT: Your performances are most successful when they become somewhat scary and legitimately risk serious injury.

SL: Absolutely. It also compromises the art viewers’ role in the space, which further compromises the institution’s position as a safe haven for viewing art. What my performance often does is challenge the safety of the viewer, not physically, but in a way that what comes next is unexpected.

HT: You’re definitely aware of your audiences and it seems like you even play off their energy, but is your relationship to the audience more complex than entertainer/entertained?

SL: The work varies with every crowd. I’ve had the chance to perform in formal art settings and I’ve also had the pleasure of creating the environment. Part of the concept—a muscular, dark-skinned body putting itself in exhibition as a spectacle—is very influenced by The Invisible Man, a novel by Ralph Ellison, which begins with a battle royal match where several African Americans are blindfolded and must fight to the finish, the winner earning a college tuition. But the idea is not only about putting myself on display. The wrestling becomes not only an exhibition, but a raw activity.

The eyes of the audience have also become very important to my performances. What I am, who I am, and how they perceive me are all important because the moment they believe in the spectacle is when I have them—as soon as they believe in the wrestling and forget the actual “art” of it is when I can flip it on them. That’s when the aggression and the pain take over. My job as a performance artist is to take you there and then to break you down so that you find yourself highly involved and emotionally invested in the performance.

HT: There is plenty of symbolism in Lucha Libre that goes beyond merely portraying a menacing alter-ego. Can you shed some light on what El Conquistador is all about?

SL: When people ask me to explain El Conquistador, I often tell them that he, or El C. as I’m now called, isn’t so much a character as he is an amplification of who I already am. It’s inaccurate to assume that wearing a mask automatically transforms me into a character. I actually think that wearing a mask allows you to be yourself more. So what you see in the ring is just me with the volume turned all the way up.

I watched a lot of Mexican wrestling with my father and related to the characters because of their skin color, but at the same time I admired the heroes of American wrestling: Hulk Hogan, the Ultimate Warrior, etc. El Conquistador is a cultural blend of those heroes. Whereas my appearance resembles those of Mexican wrestlers, my gestures, poses, and movements are more similar to the American wrestling heroes from my childhood.

HT: Given your dedication to these forms, how important is the authenticity of the performances to them? There seems to be a tremendous level of commitment and training in the months leading up to a match.

SL: As a performance artist, I hate the idea of posing. And as a former college athlete, I found I could pull this stuff off authentically. The training and preparation is becoming as important as the actual performance. But more than anything else, it’s about gaining the right focus, which involves becoming this person, not as an actor, but genuinely through becoming a boxer or wrestler. It becomes so intense that I often lose track of where the performance begins and where it ends.

HT: I’m both a big sports fan and an art fan, but my association with the two fields is unlike yours. When do athletics end and art begin for you, or do you see no difference?

SL: Sometimes I forget, or I just don’t know. The funny thing is that while learning art in high school and grad school, I never imagined that the two fields could cross. In my undergraduate days I consciously kept them apart simply because my locker room personality was very different from how I acted in the studio. I think they really began to collide when I decided where my work was going. It just felt more sincere to bring my athletic life into my work.

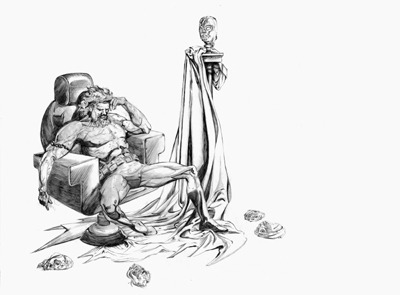

HT: How do your paintings and drawings, which are more comic book-inspired, relate to the performances and the other aspects of your work? It seems that a defeated sense of heroism looms over everything.

SL: The paintings and drawings become much quieter and more strategic in the face of the performances because performance has become more of a cathartic expression, where I just let loose. What truly ties all of my work together is the overwhelming sense of failure as the outcome. My self-portraiture within the artwork and the self-portraiture within the performance work always contains the idea of falling short because each is about the idealistic idea of hyper-masculinity that is impossible to attain.

HT: You’ve previously written that pop culture and the media constantly exalt stereotypical aspects of masculine behavior. This is never more true than in times of war, when the idea of sacrifice is linked with heavy artillery.

SL: The interesting part of it is that within the art world there’s such a pretense of negating the very idea of heroism or of being super-critical of those intentions from the outset. I believe some of these people are hypocritical. Because while many people in the arts are critical of over-the-top heroism, I feel that a lot of them desire to be just that. It’s just that in the art world it’s easier to go with the prevailing wind. There’s a distrust and desire in my work and that’s where the truth comes across. I can critically examine these icons and my personal histories in them, but then I realize that a lot of that is me and sometimes I want to be those heroes.

HT: How will it all end for El C.? I wonder because your supposed last match in character will take place in September in Corona, Queens as part of the Queens Museum of Art’s Corona Plaza, Center of Everywhere: Four Site-Specific Projects. It will be a different audience than you’ve previously had; not only will it take place in the middle of a public plaza, but most of the residents and business owners there are Mexican and Latin American and are very familiar with Lucha Libre. What do you expect the whole experience to be like?

SL: I’m really scared [laughter]. The idea or the art of it could be really lost in that community. Putting that aside, I’m incredibly excited to have the opportunity to perform in front of a community that I attribute much of my identity to. I grew up in a very similar area near Corona—Forest Hills. I know the area; it feels like home to me. The challenge that I’m looking forward to is winning them over. But it will be completely different from past performances. I feel that this performance, which will likely be the last time that I perform as El C., will have the perfect sense of closure because it’s not necessarily about the art or the conceptual underpinnings of me fighting The Invisible Man. Rather, it’s about coming home as an artist and performing in front of a hometown crowd. Also, the very essence of this performance was to look at myself not only within this mold of masculinity but truly battling the invisible perception of myself.

HT: You talked about going home again. I’m curious as to your cultural upbringing as a New Yorker especially as it relates to the subject of identity politics in your own work.

SL: Well, I completely accept identity politics because I feel I am in the gray area. I’m half Dominican, half Guatemalan. Both my parents came to New York to study. Queens is such an amazing place because you can be proud of your heritage, but at the same time you are completely lost within the diversity. It’s the unknown experience of identity politics—to be something and nothing at the same time. And that’s precisely what much of my work is about. I grew up American. I only learned Spanish in my teenage years. But I was raised in both worlds and can sort of be fluid in the two. The complexity of growing up within the diversity of Queens allows you to reach out to many communities and attach yourself to different experiences. I related to the Black communities, to the Indian communities, to all sorts of different Latino communities. Yet it was the complete opposite of that when I went to high school in the Upper East Side. There, it didn’t matter what country I was from; I was just different.

HT: In relation to white students?

SL: Exactly, in terms of being in a predominately white environment, where there was a lack of exposure and understanding of my background. It allows you to have a hyper-conscious perspective of who you are. It was completely opposite from growing up in Queens because I wanted to be more definitive about my heritage in the face of ignorance. I’ve had this unique pleasure of being in multiple worlds at the same time and configuring my identity in the face of all of it. This complexity is not portrayed in the identity politics of the art world because artists want to take a particular stance. They need to carry specific definitions: “This is who I am,” or “This is who I want you to see.”

HT: The way you’re talking about it is that all of those things are important in the formation of your identity, so that in the end there’s nothing to attack.

SL: Yes. I also don’t need headings or chapters. I no longer find it necessary to figure it all out. Identity can be fluid and shape-shifting.

Shaun Leonardo’s current solo exhibition at Real Art Ways in Hartford is on view through July 1. He is represented by Rhys Gallery in Boston; and March Gallery in New York, where he will have a solo exhibition opening September 5. Leonardo’s work will also be included in Corona Plaza, Center of Everywhere: Four Site-Specific Projects.

Herb Tam is a curatorial consultant at the Queens Museum of Art for which he is organizing Corona Plaza, Center of Everywhere: Four Site-Specific Projects, opening on July 1st.

For more information on Shaun Leonardo, visit:

www.elcleonardo.com/