The Business of Art: The New Exchange Rate

Several new projects are building an alternative to traditional modes of art funding

In early ’70s New York City, when artists were still paying their Max’s Kansas City tabs with paintings, there was also, for a time, Food, the SoHo artist-run restaurant co-founded by Gordon Matta-Clark. Food’s open kitchen turned cooking into a performance and a meal into an event in which diners might return home afterward wearing cleaned bones, souvenirs from that night’s menu. No one is walking around with bone bracelets today—at least not yet—but a similar spirit has surfaced once again in the art world, with several new projects utilizing innovative approaches to funding, relying on the community as a resource and sustainability as the ultimate goal.

FEAST (Funding Emerging Art with Sustainable Tactics) is one of them, billing itself as “a recurring public dinner which democratically funds new and emerging art makers.” Hosted in the basement of a Greenpoint church, diners pay a sliding-scale fee for a meal, and the chance to consider and vote on various artist proposals. The evening’s collection is divvied up among the proposals with the highest number of votes. Recent grantees include Dan Funderburgh for Home Front: Habitat Decoration Initiative, a neighborhood beautification project using his custom-made wallpaper, and Joey Zvejniek for Hot Dog Hot Dog, for which the artist gave away free hot dogs (or drawings of them) in a Bushwick park for a day.

FEAST is building an alternative to traditional modes of art funding, though not surprisingly, the volunteer collective behind it is predominantly composed of people with day jobs in cultural and art administration. Their models are farm shares, not Guggenheim grants. One volunteer, Jeff Hnicka put it this way: “In food, the cycle runs like this: I give money to a farmer, the farmer gives me produce, I make food, create waste, compost, start a garden. With art funding, typically what happens is you go outside the practice, write a grant, and there’s a limited relationship between the artwork, the funder, and the artist. At FEAST, the people get a say in what gets funded, and they get to later see the work that was voted for, and so they complete that cycle.”

The first FEAST was held in February, and subsequent ones have run at capacity, feeding 125, and making enough money at the door to fund multiple proposals. Partially inspired by the similarly run InCUBATE Sunday Soup Brunch in Chicago, FEAST hopes to help create a system that’s repeatable in other situations and communities.

The first FEAST, held on February 29, 2009. Jeff Hnicka (right), offers winning artist Dan Funderburgh $756 to fund his neighborhood beautification project.

Antonio Puri’s Art4Barter Project, a series of exhibitions whose works are for trade, not sale, is one such repeatable system. The project has traveled to galleries in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and New York, and is set to open soon at New York’s Tamarind Gallery and in June at a space in Chester County, PA. The exhibits happen like this: Puri gets a gallery to agree to host the show, and curates work by artists who are willing to put up their pieces for a fair trade of goods or services.

“Regardless of how big the art world perceives them to be,” says Puri, “these are respected artists who still have needs that aren’t being met.” Affixed to the wall next to each work is a label listing the artist’s terms of trade, which might include website design, gas money for a cross-country trip, a digital camera, or “other offers.” The artist negotiates the exchange directly with the interested party. This process, says Puri, breaks down cultural backgrounds. “It’s like, ‘I’m an artist, you’re a plumber,’ or ‘you’re a doctor; let’s talk.’”

There’s also the scenario of, I’m an artist, I have a pile of “money” hand-drawn by children and people from all over the country—hey, Congress, let’s talk. That’s the basic idea behind Mel Chin’s Fundred Dollar Bill Project, a response to a long-running crisis in New Orleans that came to Chin’s attention in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

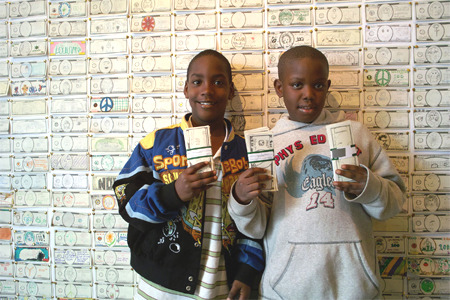

New Orleans’ children, rolling in" fundreds" for Mel Chin’s Fundred Dollar Bill Project.

“The conditions were intense,” says Chin. “Not just the physical aspect, but the emotional, psychological, sociological devastation that is still there now. I left traumatized because I didn’t have a solution to that.”

Chin began researching, honing in on particulars, and discovered that New Orleans had, even before the storm, been the second-worst lead-polluted city in the country. (The worst is Cleveland.) Lead levels in the city’s soil are so dangerous that thousands of children are at high risk for severe learning disabilities and behavioral issues that often lead to violence. No money has yet been allotted toward reversing the problem; such a project, Chin learned, would require approximately $300 million. “In terms of art, that’s a lot of money…it’s an engineering project—the cost of a bridge. I couldn’t raise that kind of cash.”

He could, however, make it—and get kids all over the country to draw their own “fundred dollar bills,” the innovative core of his latest artistic undertaking. The Fundred Dollar Bill Project works in tandem with Operation Paydirt, a partnership of scientists, teachers, engineers, health professionals, urban planners, and artists working together to determine the best way to try to combat the lead issue.

Mel Chin’s Safehouse, whose walls are covered with “fundred dollars."

I’m not saying that lead in the soil is the cause of all of the problems, but it is at an unacceptable threshold,” Chin says. “And so what we’re after is a barter of ideas, of science. Children can’t vote, but they can express themselves in a form that is itself a valuable expression, one that we can collect and use to start a conversation, to deliver a message.”

In Spring 2010, an armored truck (running on vegetable oil, refueling at school cafeterias) will deliver all the fundred bills gathered from collection points all over the country to Washington, D.C.; the project will then publicly request from Congress an “even exchange” of $300 million allocated toward enacting Operation Paydirt’s solution to the lead-pollution problem. Already, talks have begun with individual members of Congress, and Chin is optimistic that his fundred bills will help buy a workable answer to some of the health and quality-of-life issues still plaguing communities in New Orleans: “We want to treat the soil, to lock it, to cover it with clean soil that comes down from the Mississippi. The poetic return of soil, or new soil, would be key to the solution.”

Rebecca Bengal has written about such things as death, design, obsessive teenagers, abandoned motels, William Eggleston, Joseph Cornell, Royal Trux, beach bums, trains, dive bars, bootleggers, destroyed theme parks, Graceland’s daily visitor, and a Russian cat circus. Her fiction and nonfiction has appeared in New York, The Believer, The Washington Post Magazine, Southwest Review, Oxford American, and elsewhere. She is at work on a novel, June Gloom, and a collection of stories. More of her work can be seen on her website, www.tvmodern.net.