Meet a NYFA Artist: David Heatley

Suzan Sherman: What did you like to draw when you were a child?

David Heatley: I’ve pretty much always had the urge to draw my version of whatever media I was consuming since I was a kid. So in early childhood it was picture books and my version of Peter and the Wolf. Then as a teenager it was Lord of the Rings,Spiderman, and Wolverine. Then Mad magazine (not the good, early Harvery Kurtzman Mad, unfortunately). And in my twenties it was “alternative” autobiographical comics. Autobio comics had an early flowering in the ’60s (with Justin Green and Aline Kominsky-Crumb) with a renaissance in the ’90s. It was during the ’90s that I started reading comics being published by Drawn and Quarterly and Fantagraphics and began doing my own hackneyed version of relationship stories and personal history narratives. I’ve stuck with it long enough to have found my own voice, but it took about ten years to get to the artistic terrain I’m on these days.

SS: You mentioned Alice Neel in your book, and David Heatley, your comic book character in My Brain is Hanging Upside Down, always seemed to be doing portraits of his friends, at least around his college years. How do the comic portraits that you did of your mom and dad—which you distinctly describe as portraits—differ for you from the portraits that you did previously?

DH: Alice Neel’s portraits were a big inspiration for me in college. Since high school, my impulse has been towards self-portraiture and portraits of the people I love. Whatever impulse it was that drove me to understand myself and the people closest to me is still very much driving my work today. I think it’s where art and psychology meet. The study of faces, expressions, emotions, personal histories…all of this is deeply interesting to me. The best portraitists capture more than just a moment in time. They seem to capture some essential psychological dimension of their subject—all that came before and leading to the moment depicted and maybe some foreshadowing of what will come after. I’ve never been a very good painter. But it was natural that these interests would carry over into my comics. In film school, I did filmed portraits of friends where I’d have them do activities or just sit and I’d film them in quadrants and simultaneously project the four images together. I thought of them as cubist film portraits. They were marginally successful. Later I started thinking, how would I make a portrait of someone in comics? And when I saw Dan Clowes’ book Ice Haven and Chris Ware’s Whitney Biennial poster, I got the graphic solution I was looking for. They were breaking up their page into smaller, discreet comic strips that related to each other to tell a bigger story. My idea was to focus that device on one subject, i.e. my dad. So “Portrait of My Dad” and “Portrait of My Mom” are a series of vignettes, which add up to a portrait. It’s amazing how much you can reveal about a person just by placing a few anecdotes next to each other on a page. Your mind fills in the gaps of what’s missing and you begin to feel like you know them. In a way, my book is one big self-portrait operating under the same principle.

SS: Comic—as in comic book—conveys that what you’re about to read will be comical to a certain extent, or at least that’s how the term comic book initially came about. Do you consider the work that you do as fitting into the comics category, or as something else, and do you think of your work as funny?

DH: I like the term comics. I’m not so keen on “graphic novel.” Though I do use “graphic memoir” for my book because in my case it’s true in both senses of the word. I think at its core, drawing comics is about making funny pictures. The atom of these drawings is the doodle. That said, I think the beauty of comics is their ability to seduce and lure in a reader with a cute veneer and then bring up uncomfortable truths. That’s what I try to do. I don’t do slapstick humor, but I do try to make what I’m doing as uncomfortably funny as possible. A lot of other cartoonists have said all this better than I’m saying it. I think Ivan Brunetti said there’s a lot of power in getting someone to agree with you about what’s funny. I try to have an almost God’s eye perspective on my life. It’s all fodder. As long as enough time has passed, it’s all potentially funny. I think when certain artists try to bring too much of a painterly approach to comics, the work really suffers. You see a lot of that in European comics, an overly earnest Cézanne brushstroke style. As though doing that dignifies the form and allows for more serious reading. In my mind, it sort of deadens everything if you stray too far from making little pictographic doodles. That’s the root lineage of comics and it’s where the form gets its vitality.

SS: What comes first—the words or the images, or does it shift? And what’s the hardest and easiest part of the process?

DH: The uphill climb is always the writing, which for me involves lots of lists, diagrams, scribbles. It’s like chiseling in stone. And there’s really no forcing it. You sit and try a few combinations of ideas and it either flows forward or there’s a roadblock and you back up and try a different route. Once I get that breakthrough where I know what will go on a given page, I can start thumbnailing it, usually in light pencil. That part is also very difficult. Because every inch of it involves decision making. I try not to agonize. I just go with my gut instinct and get the first quick doodle down. And that usually stays. But sometimes there’s a lot of editing for space requirements. “I need this strip to end on this page…. how essential is this panel? Can I collapse these two into one?” That kind of work can also be painstaking. Once I have the whole page pencilled, there’s a sense of relief. I can read it through and see how it reads and feels. After that, the work becomes more about craft, which is fun. Inking the page, scanning it, coloring it on the computer. These go really quickly for me. And I can usually estimate a number of hours on each and stick to that. There’s pretty much no estimating the writing time though. It has a life of its own.

SS: A number of the comics in My Brain is Hanging Upside Down are dream memories. What interests you about conveying your dreams in comic format?

DH: In the mid to late ‘90s, I was inspired by the dream comics of Julie Doucet and a dream-based strip by Dan Clowes called Nature Boy. I later discovered Brad Johnson’s work, which operates under a similar, hazy dream logic. When I decided to take the comics I was making more seriously, I realized that all the best ones I was reading had a solid architecture of good storytelling underneath the art—the best cartoonists are always primarily writers and use their art in the service of their narratives. When I first started out, I knew nothing about writing fiction, but I did have almost ten years worth of journals dating back to my teen years. Once I started reading them with the intention of making them into comics, the dreams really stuck out to me. They were spectacularly disturbing, symbol-ridden, and deeply personal. They were a synthesis of all that I was thinking about and longing for, and they were already written. All I needed to do was illustrate them. I’ve probably done about 30 of my dreams at this point, some of which have made it into My Brain…

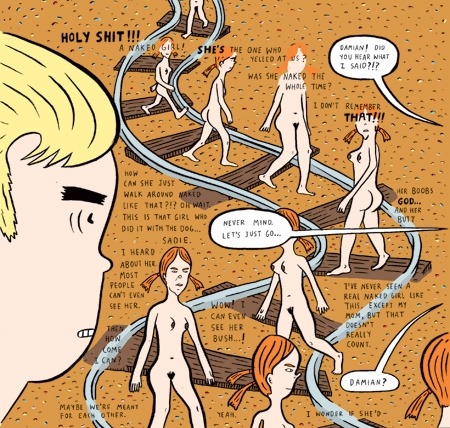

SS: Overpeck—at least what I’ve read of it so far—has that dreamy quality spread over the whole narrative. How do you see it as being similar and different from My Brain is Hanging Upside Down?

DH: The first comic book I did was called Deadpan, and was entirely made up of dream comics. I began to branch out and tell other parts of my story—illustrating my whole sex history, doing a comics portrait of my father. Eventually I added my mother’s portrait, a family history strip, and a strip about race called “Black History.” All of that autobiographical material is in My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down. While working on what became that book, I had the idea of starting a fictional story. While talking to a cartoonist friend named Kaz, I mentioned that I didn’t know how writers came up with their characters. He pointed out that my first comic book was filled with characters that I had dreamt. They were already invented. I just needed to flesh them out. I drew little pictures of each of them and started making notes and found that I instantly knew their names and what their personalities were. Overpeck is the name that I gave to the town where all these characters live. Some of the story is based on my old neighborhood in Teaneck, New Jersey, where I lived from kindergarten through second grade. Those might have been the most formative years of my life, and they’re where I draw all the inspiration for writing Overpeck. It’s basically a story about childhood sexuality, trauma, and recovery. There’s a spiritual awakening that happens at the end of the book. The whole story is still very much in progress. If all goes as planned, it’ll be my second book from Pantheon. Maybe in 2010.

SS: Overpeck has such a different look than My Brain is Hanging Upside Down. Why the shift from small, tight boxes to a more expansive style?

DH: A lot of My Brain is done in a very sketchbook/diary style. I wanted it to be obvious that it’s my story. Every letter, every wobbly drawing, comes from my pen and says something about me and my psychological state. Because it’s fiction, Overpeckis an attempt at a more detached approach. I’m very inspired by a Japanese cartoonist named Shigeru Sugiura, whose page and panel layouts and character design are wildly idiosyncratic and expressive, while still looking very controlled and cute. So that’s what I’m attempting with this style. I’m following a strict 25 panel per page grid, but I often break it open into a half-page vista, or even a full-page or double-page spread. It’s about creating a sense of location by showing the details of the town.

SS: In My Brain, I love how in the midst of some very raw memories of your childhood and adolescence you have these much more sophisticated takes on the music that you were listening to at that time. It allows the more adult David Heatley into the story, and for the past and present to meld…

DH: While making notes, I realized that I wanted to include the music I was listening to. Hip hop, for me, is one of the most miraculous art movements that’s ever existed. As Mos Def says, you take some teenagers from the projects in the Bronx, who aren’t even supposed to have one good idea, and they come up with break dancing and rapping and graffiti. All of which are now multibillion-dollar industries. Hip hop was, and still is, tremendously important and inspiring to me. I wanted to honor the music I was listening to by including it. Some of the record “reviews” in there are really about the experience of hearing the music for the first time. How the child heard it. And later, as I grow up in the strip, I start getting more critical in my taste and appreciation, so the reviews get a little more complex. De La Soul, Jungle Brothers, and A Tribe Called Quest altered my consciousness forever. They’re all heroes to me. And they hit my town like an atom bomb when their albums dropped. The excitement was palpable. It was a powerful experience for me to own how strongly these records influenced me and to honor that I might have something to say about them—to contribute to the dialogue, not just passively consume or co-opt this stuff.

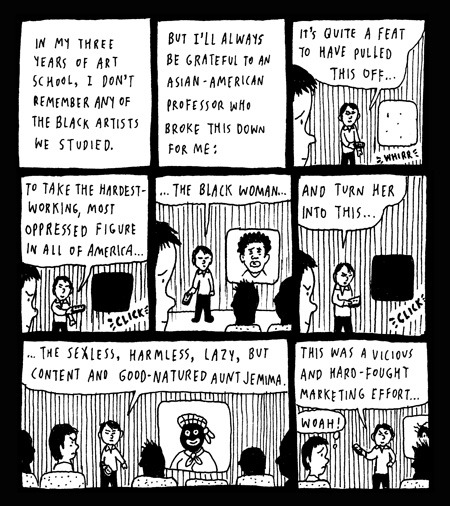

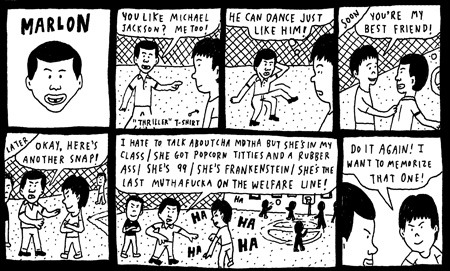

SS: In the “Black History” section of My Brain you’ve conveyed lots of stereotypes about black people—as being dirty, stupid, smelly, poor, cool, overly sexualized, and rendered them with huge mouths and genitals. Are you at all concerned about being accused of racism?

DH: I was born white in this country, so I have racism in me. It didn’t help that I was beat up by a group of black kids at my first preschool. But I would have had most of these thoughts and feelings anyway. I’ve been conditioned. I knew I wanted to do a strip about race. Just like I realized how unique my dreams were and what a great subject they’d be for art, I had a similar appreciation for how racially integrated my childhood was. I grew up and went to public school in a town with a large black population. I also went to a religious sleep-away camp with kids from all over New Jersey, including a large group from the inner cities of Newark and South Orange. When I was in high school, a black kid was shot by a white cop in my town. There were riots in the streets. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton came and held rallies. This isn’t the average suburban white kid’s experience. So I knew there was lots to explore. I also knew that it would be pretty shocking if I spoke as candidly about race as I do about sex in my book. White people seem to be either cagey about discussing race at all or are cavalier and oblivious about their racism. There’s a lot of fear about being misperceived. I’m not really afraid of that. I quote Malcolm X (who is one of my heroes) in the beginning of the strip, “I’m for truth, no matter who tells it.” I’d be thrilled to read an honest account of what it was like to grow up black in my town (Mike Kelly does his best to tell some of that story in Color Lines). I can only write what I know, which is what it was like to be white in that town, and everywhere else I’ve lived. The way that you’ve worded your question, my comic sounds pretty bad, but I’d say that for every character that might fulfill one of the stereotypes you listed, there’s at least one immediately following it who is the opposite. Many of these characters were close friends of mine, not people observed on the surface, so there’s a lot of complexity there. Ultimately, I think my thesis for the piece goes something like, “If I group all the black people I’ve ever known into one comic strip, can I make any generalization about them all?” And the answer is no.

SS: Throughout My Brain, pink rectangles cover the genitals of your nude characters. Was this your publisher’s idea, or your original drawing concept?

DH: It was my idea. I originally published the strip with very graphic sexual imagery and Pantheon was happy to publish it as is. Over the last few years, I received some fan letters from twenty-something boys saying “I loved your story, it gave me a boner!” That was not my intention. While repackaging it for the Pantheon book, I was feeling like all that genitalia was getting in the way of the story, which is about bad sex and longing for connection. Not erotic titillation. My solution was to paste neon pink rectangles over all of the genitals. It adds another layer of narrative because it calls attention to itself in a funny way.

SS: Are you at all fearful of how you will be perceived? You’ve let your brain hang out in all its honesty—and your book is disturbing at times.

DH: I try not to be fearful about anything these days. I feel pretty sure some people won’t like my book and some may feel even stronger than that. I had a writing teacher in art school who always asked us “What are you willing to risk?” What’s the point of writing something if you’re not willing to make yourself vulnerable? Why would anyone want to read it if I wasn’t putting myself out on a limb?

David Heatley is a cartoonist and a musician. He is the author of the upcoming graphic memoir My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down, to be published by Pantheon and Jonathan Cape in September. An EP of his book’s “soundtrack” with an accompanying music video will be released on iTunes in October 2008. His comics and illustration work have appeared on the cover of The New Yorker, in the New York Times, and in numerous anthologies, including Best American Comics 2007,McSweeney’s #13, and Kramer’s Ergot. Heatley is a recipient of a 2008 NYFA fellowship in Literature. His website is www.davidheatley.com.

Images: From top, My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down (2008) (1, 2, 4); Overpeck (in progress) (3).