Meet a NYFA Artist: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

NYFA talks to Margaret Inga Wiatrowski (2011 Printmaking/Drawing/Artists Books Fellow) about her trajectory as an artist and the influence of Hurricane Sandy on her work. She also contextualizes some of her new work on display at NYFA and chashama’s After Affects: Hurricane Sandy Exhibition.

NYFA: Has creating art always been a focus in your life? When and how did you decide to become a professional artist?

MIW: I can’t say there has ever been a particular moment of decision, only a continuous attempt to realize the goal of art-making in any capacity, under invariably shifting circumstances. I’ve spent my life involved in the arts, although the pursuit of art as a career objective has been primarily through nonlinear paths and nontraditional means. I recognized, even early on, that it takes enormous amounts of unrestricted time, effort, and perseverance to create work, and I understood there would be serious difficulties in being able to craft a livelihood that would allow for that type of dedication; so it’s been an enlightening, albeit meandering path, for as long as I can remember. I’ve gone through an abundance of self-doubt about how to make work, make sacrifices, take risks, and how to organize life around being able to make that work. That’s been a work in progress, always. So while the trajectory hasn’t always been neatly outlined, I’m very encouraged, and optimistic about continuing to carve out my own path.

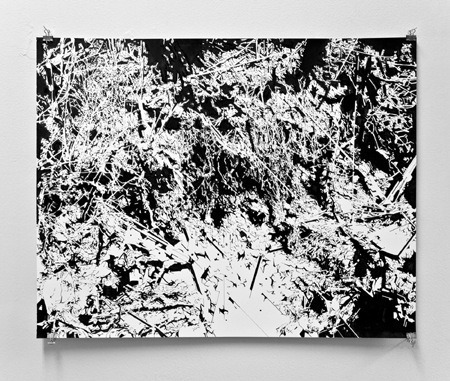

Aberrations: No.20

Photo Credit: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

NYFA: You studied English Literature and Communications Design during undergraduate and graduate school, respectively. How would you say your background in literature and design has influenced your creative process?

MIW: Both courses of study were fundamental to the work I’m creating now, and although not the likely academic directions most artists take, they broadened my artistic literacy in ways that have proven to be invaluable. When you study literature, you end up studying a broad nexus of all the liberal arts; it’s a way to further an understanding of topics that have to do with all aspects of human society, culture and art, another way to understand and engage with humanity, and to articulate ideas. That allowed for a type of freedom in critical thinking and training outside of the classic art school program, which greatly influenced the way I approach and consider my work, as well as how it’s created. From graduate school I took a bevy of contrasting applied and conceptual skills. The principles of design, for instance, are ingrained in my drawings, as are the principals of narrative and storytelling, even if they are not immediately visible. Ultimately, I’m very grateful for having what I believe to be a rich, unique background to inform my work. It’s a knowledge base outside of areas typical to most artists, and the histories, practices and methodologies of each discipline permeate through everything I make, endowing it with added dimensions I would not have arrived at through conventional ways and means.

Aberrations: No.18

Photo Credit: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

Aberrations: No.17

Photo Credit: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

NYFA: Many of your photographs and drawings emphasize subtractive forms by which fragile, obscure and ephemeral places are accentuated. How are drawing and photography linked for you?

MIW: Most of my photographs are constructed scenes; they’re artificial environments that employ traditional sculptural techniques and include found objects as well as elements of natural life in the compositions. However, as I started building scenes that were larger and more involved, I needed to plan them out more carefully, so I turned to drawing to help define them. Initially, the drawings functioned only as modes of visualization: renderings for the yet-to-be-made sculptures. Like conceptual blueprints, they provided the initial infrastructure on which the next stage of three-dimensional, constructed pieces would be built.

Although my method of drawing often takes far more time to produce than the photographs, I think the wandering, problem-solving and detail-oriented mapping of the terrain-to-be, has proven to be especially necessary in more ways than just serving as preparatory renderings. I like that they speak quietly, with delicate expression, and in the past few years I’ve spent much more time with them than ever before, often abandoning a photographic objective, favoring the slow pace of the process for its own purposes, as well as the antiquated inking techniques used to achieve them. Drawing in this way is an act that privileges time spent, mindfulness, and labor-intensiveness as worthwhile endeavors in their own right. It takes a turn away from the reality of fleeting things (the flickering nature of the digital sphere, the preoccupation with immediacy, the gradual transition away from physical objects to their electronic equivalents), and allows for the opportunity to experience a spell of stillness, that rare quality, to create moments that exist beyond temporality.

Although the drawings often do not visually correspond to the eventual photographs in an obvious way, it’s the act of thinking abstractly that becomes the most gratifying aspect of the process. It’s a slow, exploratory exercise that mirrors the subject matter in many ways, creating an opportunity for moments of detachment, where the empty space of a blank page offers a place where meaning can be constructed by connecting disparate elements, moments, and graphic details.

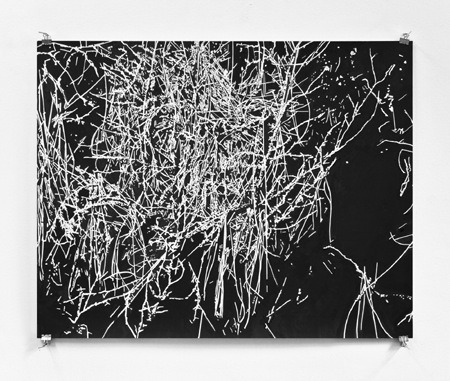

Negativland: No.02

Photo Credit: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

NYFA: You were awarded a NYFA Fellowship in 2011. How would you describe the evolution of your work in the past few years since getting a fellowship? What would you say has most influenced it?

MIW: The 2011 fellowship allowed me to not only to continue my artistic endeavors in the most fundamental sense with financial support, helping to secure much-needed materials and supplies, but it also helped bolster the development of my work with an encouraging jolt of self-assurance. It allowed me to work with a resoluteness that wasn’t quite there before, and with a focus on creating work with depth and breadth that I had not previously devoted to it. Working in a studio space that the grant helped facilitate, I’ve also been able to steadily expand my capacity for experimentation and production, using the space to start building sets and sculptural elements for a new series of constructed photographs. However, the freedom I was afforded by just being able to create work consistently in the studio, made the most profound difference. I continue to be deeply grateful to NYFA for breathing life back into my creative process, for continuously presenting multiple opportunities for developing relationships with a broad community of peers and the art world at large, and for being a bedrock of support in times of exceptional need, as was recently the case with hurricane Sandy.

NYFA: Speaking of Sandy, you recently received funding through NYFA’s Emergency Relief Fund. Can you talk about the impact the storm had on your space and your work and how you plan on using the funding?

MIW: The storage space for both my independent employment and my art practice was located in a basement in Chelsea and was completely submerged in the flooding that occurred during the storm surge. My studio isn’t an expansive space, so the storage facility contained the bulk of tools, materials, and inventory that were used both for art-making and my freelance employment, and I lost everything in that space. Along with completed and framed work, I lost drafting tools, calligraphy supplies, paper stocks, frames, a library of reference books, photographic equipment, a decade of negatives and photographs, electronic equipment, among other things. The funding I received has gone directly to recouping those losses as much as possible, beginning with the most essential supplies. I’m so thankful for the relief extended to me by NYFA beyond simply extending financial resources. The generous support offered by NYFA also provided invaluable solace in a time of personal and professional hardship, and has already made a significant difference in my ability to continue to create work. The funds will be especially far reaching in the coming months as I begin down the long road of replenishing lost inventory.

Negativland: No.42

Photo Credit: Margaret Inga Wiatrowski

NYFA: You have said that your photographs document “environments overtaken by impossible or strange accidents” and that you are “primarily concerned with themes of obsolescence—narratives of transience, transformation and loss”. Has the recent destruction caused by Sandy influenced your ideas on these themes?

MIW: The hurricane and all the changes it brought with it, coincidentally, exemplify many of the ideas expressed in my most recent work. I’ve always been interested in places that seem to be perpetually in a state of disappearing right in our midst–and the vulnerable, anxious, ever-changing landscapes of our own urban geography very much fit into that realm of interest.

New York City in particular–it’s a place with so many layers of history– full of memory, stories, and half-forgotten remnants of a past that feels charged with some indefinable energy that lingers in every urban relic you come across. Nevertheless the city and its surroundings change so quickly I can hardly keep pace: places disintegrate, they are torn down, lifted up, cleared out, excavated, eroded, built over, destroyed and continuously redefined. These surroundings feel so ephemeral and fleeting, and in some ways, I suppose I’m always attempting to try to retain something, to salvage something from the irreversibility of time, and to rescue some memory of these places before they vanish. Sandy’s recent destruction has only heightened that sensitivity, and the feeling that, when you wander through the city, especially areas around the water–they are fragile and diaphanous, and quintessentially transient.

NYFA: We look forward to seeing your work in the upcoming NYFA / chashama exhibit, “After Affects”. Will you discuss the pieces included in the show and contextualize them for us?

MIW: In the weeks after Sandy, my apartment was without power, and I was without work, so I spent a considerable amount of time wandering around the city on my bicycle, doing a lot of looking, and drawing in the studio. On my mind were the images that were being shown of the wreckage in Breezy Point, Staten Island, New Jersey, among others, and I was reminded of the time I had spent, not too long before, in some of those same places, how quickly it all unraveled, and how tenuous it felt, even before the storm–places that were already in some constant state of flux, or otherwise so unprotected, so exposed–landscapes rich in associations between what is fixed and what is now, in some cases, somewhat placeless. The city looked suspended in time, and the images that were being shown in the media of these aftermath environments looked like modern ruins to me, with few settings that could be easily identified. There was the awe of vanishing materiality– and I couldn’t help but think, at the time, that these landscapes changed without any sense of forthcoming possibility. They made me think of a past that could have been and a future that never took place.

In the studio, I spent time recollecting, specifically, the watery areas that linger on the peripheries of the city; referencing old photos I had taken and relying on my memories to recreate impressions of those places that had some significance to me at the time, and thinking about what happens when the places where you once followed your whims suddenly disappear. In particular, the two pieces included in “After Affects” recall the areas around the Rockaway Peninsula, places I had spent a lot of time exploring years before the storm. One, a wild, wooded area in Fort Tilden that always felt a bit out of time, out of place, and the other, a slowly eroding beach, where pieces of it were already being lost into the ocean daily. There’s a strange relationship between our memory of a place and its representation in our imagination, and these two locations, especially after seeing coverage of these sites after the storm, evoked a peculiar quality. Central to each image, lies some sense of disorientation, but despite that, there’s also a sense of resistance, and I’d like to think that both drawings record half-realities of those places– both in the midst of falling apart then, and transformed beyond recognition now– stills of what appears to be a landscape that has changed rapidly into an unknown and alien territory, revealing an impermanent world where everything is changing, whether we notice it or not.

—Interview by Lara Hidalgo

For more information on Margaret, please visit her website.