The Business of Art: A Representation Gap

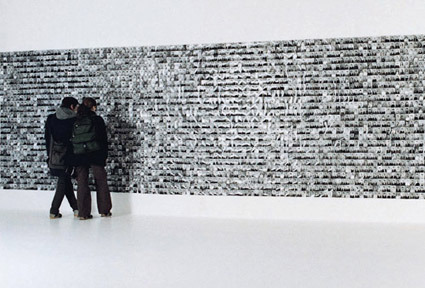

Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari. Installation of i.d. photos from Studio Anouchian, 1935–70, Tripoli, Lebanon (2003). Photographer: Antranik Anouchian. Installation view, House of World Cultures, Berlin (2003). © Arab Image Foundation, W. Raad, A. Zaatari. Courtesy artists and Grey Art Gallery, New York.

Although the prominence of the Middle East in political rhetoric (and action) is affecting the amount of work by Middle Eastern artists American audiences see, a problem remains. US-based Middle Eastern artists often gain prominence and are shown more frequently internationally. Are American curators not proposing sensitive and thorough shows involving Middle Eastern artists? Are American institutions threatened by the nature of their work, which is frequently critical of American political policies? Or, more grimly, are both true?

An online article in the January 26 issue of the Beirut Daily Star entitled “Promoting an Alternative Image of the Arab World” notes that in 2004 artist Mona Hatoum, poet Mahmoud Darwish, and architect Suad Amiry were all recipients of prestigious European awards, supposedly based on merits and not the contemporary politics that have thrust the Middle East very much into the spotlight of the western world. Similar opinions were echoed in 2004 when Zaha Hadid, the Iraqi-born British architect, became the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Even if such awards are politically motivated, they don’t negate the worthiness of their recipients, who are pioneers in their respective fields and have been producing remarkable work for decades. A more pressing issue to consider might be whether such recognition is capable of altering the effects of vast representational imbalances Middle Easterners have been experiencing in the US, culturally and otherwise, for over a century.

Much like the delivery of news on the Middle East in the mainstream media, curatorship has recently lacked when it comes to mediating works by artists from this region. Without nuance, the translations of work by Middle Eastern artists risks confining its legibility to the ghettos of the contemporary art world instead of reaching larger audiences. A brief overview of recent visual art trends (biennials, mid-career surveys, and thematic exhibitions) demonstrates a growing interest here in the works of Middle Eastern artists. But the translatability of this delayed and somewhat sporadic reception within a market-driven international art scene and its corresponding “global” aesthetics also reveal certain patterns which beg some questions and pondering. Namely, US-based Middle Eastern artists usually gain recognition in Europe and elsewhere before the stamp of acceptance comes from cultural institutions in the US.

For example, until the 1997 New Museum’s opening of Mona Hatoum’s 15-year survey exhibition (organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago), the artist enjoyed much broader recognition in Canada and Europe, despite—or maybe because of—the more overtly political content of her earlier performance work. Similarly, New York-based Egyptian artist Ghada Amer, known for her painstakingly stitched canvases that appropriate pornographic imagery from popular culture, was shown at the Istanbul, Johannesburg, and Venice Biennales (1995, 1997, and 1999, respectively) before significantly cracking the US art scene in 2000, when she was included in the Whitney Biennial; P.S.1’s Greater New York; and had solo shows at Deitch Projects, New York; and the Institute of Visual Arts, Milwaukee. The majority of New York-based Walid Raad’s Atlas Group exhibitions between 2002-2004 were international. Emily Jacir’s now-iconic Where We Come From series, in which the artist (who possesses an American passport) performed favors for—and the fantasies of—Palestinian citizens who aren’t privileged with her freedom of movement, recently came under a scrutiny in the US that it didn’t face when it was shown at the 2003 Istanbul Biennial. Earlier this year, away from cosmopolitan centers, the Jewish Federation of Kansas pressured Wichita’s Ulrich Museum of Art to place brochures and a sign expressing their views in the gallery where Where We Come From was scheduled to be shown. A nationwide letter-writing campaign succeeded in convincing the university to withdraw their decision.

It’s perhaps because of such controversies that the University of Illinois’ Krannert Art Museum’s group exhibition Beyond East and West: Seven Transnational Artists references the region without naming it, but expands its geography by including a US-based Pakistani artist and a British-born, part Iraqi artist. It might be worth mentioning that five of its seven artists were part of a Middle East diaspora(s) exhibit called Between Heaven & Hell (which I conceived in 1994) that was unexpectedly canned (along with its curator) by the organizing institution after it had received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and the NEA. The curatorial premise of Between Heaven & Hell (which has been available online for nearly a decade) also reverberated in the promotional materials of the more recent exhibit.

Granted, the term “Middle East” has been problematic since its colonial inception, but to render it invisible—even if just in the “packaging” of a touring exhibit—speaks to an erasure or denial of sorts. To substitute the term “diasporas” with yet another charged term, “transnational,” doesn’t help us unpack our (mis)understanding of the Middle East, either. Just as projecting a different (imaginary) cartography avoids the pitfalls of (actual) geopolitical remapping of the region. Don’t such assumptions affirm that post-colonialism has produced what some call “imperialism without colonies”?

Though mediating through languages outside their own, during the last decade a number of Middle Eastern diaspora artists and cultural producers have finally gained legitimacy within the competitive and territorialized space of the international art world. Run by a circuit of cosmopolitan dealers, collectors, curators, art publishers, and intellectuals, these artists’ works are curated, brokered, managed, and written about in ways which confront us with familiar questions: who represents whom? How is a discourse framed? What happens to national and cultural specificities (including ethnic minorities in the region such as Azeris and Kurds) in homogenized “global” exhibition practices? Are the production and dissemination of these forms of knowledge available to broader audiences, including Middle Eastern communities living in the West?

The internationalization of contemporary art by Middle Easterners living in the West began nearly ten years ago, even though the westward migration of Middle Easterners can be traced back to the end of the Ottoman Empire and the following remapping of the region by European colonial powers. The tragic survival story of the Armenian-American painter Arshile Gorky (and the lesser known sculptor Raoul Hague, Gorky’s compatriot and contemporary) stands not only as a testament to the era’s grand project of Modernism (the formation of nation states, displacement of large populations, ethnic cleansing, and genocides) but also to the relegation of art to exile and the struggle for survival. No wonder such experiences found expression best in the homogenized aesthetics of abstraction.

Currently, the inclusion of Middle Eastern artists within the art world’s “mainstream” doesn’t equate to the more committed integration of broader representational concerns. Without conscience-formation, exhibitions, biennials, and prizes risk becoming markers of passing trends, void of meaningful currency and vulnerable to the changing appetite of shoppers in the expanding global art malls.

Neery Melkonian is an art writer based in New York. She was formerly Associate Director at the Center for Curatorial Studies Museum, Bard College, and the Director of Visual Arts at the CCA in Santa Fe. She spent the last five years producing art-based projects in the war-torn and disputed enclave of Nagorno Karabagh, Armenia (arbitrarily annexed to oil rich Azerbeijan by Stalin). Melkonian was born and raised in the Middle East to parents who were survivors of the Armenian genocide and immigrated to the United States, where she pursued graduate studies in art history at UCLA.