The Business of Art: A Conversation with Clarinda Mac Low

Clarinda Mac Low in an early version of Cyborg Nation at AUNTS: “i believe in you” performance event (2008)

Clarinda Mac Low grew up in the avant-garde arts scene that flourished in New York City during the 1960s and ‘70s. She began performing with her father, the Fluxus poet and composer Jackson Mac Low, at the age of three, and shortly thereafter performed in Meredith Monk’s 1971 Vessel. Upon graduating from Wesleyan University in 1988 with a dual degree in dance and molecular biology/biochemistry, Mac Low began presenting her hybrid art works in New York City. For the past several years her work has focused on site-specific performances and installations with an emphasis on community, collaboration, antimaterialism, and science. Her current project, Cyborg Nation, is an interactive cyborg prototype for performance, one that will allow audience members to participate as co-creators by accessing the cyborg via cell phones or the Internet. A mobile and mutable project, the first installment of Cyborg Nation was presented at the performance party AUNTS and the second installment will be in the home of an audience member.

In keeping with Mac Low’s interest in mediating intimacy, I spoke to her via video chat and cell phone while simultaneously recording the conversation on an iPod.

Andrea Kleine: I was interested in how this project fits into the trajectory of your artistic practice. You have a background in choreography and site-specific performance, and with Cyborg Nation, the site-specificity seems to have become your body.

Clarinda Mac Low: Choreography was always a bit of a misnomer, except maybe in college and the year after. As soon as I did my first big piece in a theater, I immediately started changing it around and creating an environment—that was really what I was interested in. I am drawn to the body, dance and moving, and physical reality. But I think it has always tugged me toward this idea of being in a real space in a real time, and not necessarily creating an isolated piece of movement art. Cyborg Nation brings together my interest in performance with my interest in technology, and my interest in living in the real world and performing. I want people to be performers. I want people to be engaged in the moment of performance. If they don’t want to be on stage, they can still be engaged by being vocally present, or they can send material (text, images, video) to the performance—engaged in that charged moment.

AK: How do you feel cyborg technology enhances presence or that “charged moment”?

CML: I don’t know if it does. In some ways I think that it doesn’t, except that it amplifies presence. These devices extend our senses—they extend our hearing, they extend our sight, they extend our sense of presence. In that sense, even amplifying a private conversation creates a charged moment because it literally amplifies it, making it available to a wider group. There is also a question I have about inner life—how do you build an inner life when you’re always reaching out? I don’t mean that rhetorically; I mean that actually, as a real question.

AK: You mean, how do you create an inner life physically?

CML: Right. We’re always reaching out through various portals, so I’m curious what our mechanism is now for creating an inner life. It’s not what it used to be, but we must have one. And if we don’t have one, we’re kind of in trouble. My inner life has shifted a lot. I’ve become more likely to be reaching out constantly than thinking or reading. I don’t know if it’s worse, but I definitely think it’s different.

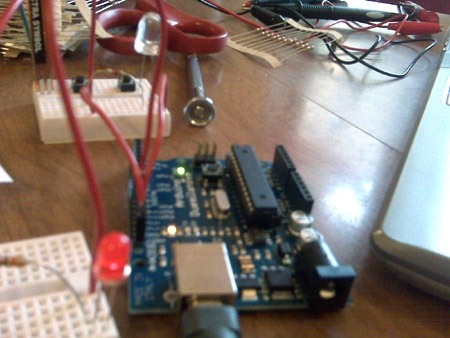

Clarinda Mac Low

Cyborg Nation (2009)

Arduino, a computer mechanism used as a trigger and/or amplifier

Photo by Clarinda Mac Low

AK: What exactly is the cyborg that you’re creating for your piece, Cyborg Nation?

CML: It’s the SCoPE, which is the Self Contained Performance Environment. That means, ideally, it would have anything I would want to use in a performance contained on the body— projectors, lights, cameras, amplifiers, speakers, a microphone, and maybe even real-time processing of information. I have a collaborator, Walter Polkosnik, who is a physicist and a systems manager and a generally curious person. He’s building a central controller—a computer he’ll be able to program so that there are sensors that trigger sound or light or video, and maybe they’ll trigger each other.

AK: What is the content of the interaction? When people call you or transmit to you, what do you encourage? Is there an idea that you want to get out of people?

CML: Yes and no. I feel like there is something very slippery about this idea. As I refine it, what I want and what I think keeps changing. I’m playing with the idea of the adaptable performance: performance as an organic mechanism that is adaptable, like an animal. The whole idea [for Cyborg Nation] started with thinking about prosthetics, about people who, through accidents, through disease, and now through wartime injury, end up having to use prosthetic limbs. We do feel handicapped without our machines. While I don’t want to trivialize the idea of the prosthetic for people who are actually trying to live without limbs, I do think there is something about how we extend our senses, and then become accustomed to those extensions, that is fascinating.

AK: I think of cyborgs as 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s science-fiction, robotic extensions of the body. But does a cyborg also extend consciousness, or extend us into the ether?

CML: Yes. That’s what I mean by our state of consciousness being different now. How do we form our inner life in this different state of consciousness? Of course I’m watching the Star Trek Borg episodes, and there’s one where they capture a Borg and he becomes cut off from the group and he’s lonely because he doesn’t have a thousand voices in his head all the time. And I feel like that’s kind of us now. We’re becoming The Borg. What would you do if you didn’t have access to all those different people all the time?

AK: And also access to data. We’ve given up things that we would have stored in our head. For example, I don’t know anyone’s phone number anymore because it’s just stored in my phone.

CML: Yes. And the same is true for knowledge. It’s interesting because it does free up your mind for other activities, since you’re not storing knowledge there. Problem solving, for example. That’s my favorite.

AK: Does your cyborg have the capacity to learn and synthesize?

CML: Yes. Absolutely. And it’s a continuing, accumulating story.

AK: What’s the life span of this project? How long are you going to do it?

CML: Well, I’ll do it until it’s done. It probably could go on for another two years. It develops and keeps manifesting in different places and spaces. It’s going to change a lot every time it happens. I think it might be finished when I pass on the SCoPE to somebody else. Once I feel like I have this thing, I have this prototype, then okay—you use it. If I can get it to that point, then my job is done.

An installment of Cyborg Nation, “Chapter II: At Home,” was presented on May 1, 2009, as part of Wine & Share, informal works-in-progress from several disciplines, at the home of Lydia Bell and Paul Rome.

More information about Clarinda Mac Low and Cyborg Nation is available on her website www.culturepush.org.

Andrea Kleine is a writer and interdisciplinary artist. She was awarded a 2004 NYFA Fellowship in Playwriting and a 2009 residency at the MacDowell Colony. She is currently at work on Throttle (a novel), Worktape 1999 (a performance piece), andDoom Jazz (a collaboration with composer Bobby Previte).

Banner image:

Clarinda Mac Low

Cyborg Nation (2009)

Diagram of the cyborg by Mac Low’s collaborator, Walter Polkosnik

Photo by Clarinda Mac Low