The Business of Art: An Interview with Impractical Labor in the Service of the Speculative Arts

ILSSA discusses its upcoming exhibition featuring innovative applications of obsolete technology

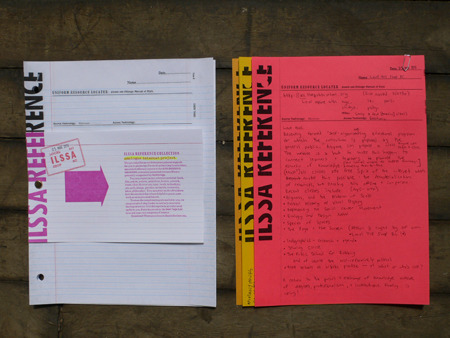

At the intersection of research institute, labor union, and social practice art project is the membership organization Impractical Labor in the Service of the Speculative Arts(ILSSA). Founded in 2008, and run by artists, writers, educators, printers, and book makers Bridget Elmer and Emily K. Larned, ILSSA is a vehicle to connect artists across disciplines who find innovative applications for obsolete technology. Annual membership in ILSSA is at an artist-friendly rate of $12 and, based on the labor union model, members become their own “local.” Members receive quarterly publications and may participate in and propose projects and exhibitions. This fall ILSSA is launching a new publishing endeavor entitled “Standards and Practices” and the group will have its first exhibition in January 2012 at St. Mary’s College in Indiana. I conducted an interview via email with Larned and Elmer, speaking here together as “ILSSA Co-operators,” about how the project came together, how it complements their own artistic practice, and where it is going next.

EW: What was the inspiration and impetus behind forming ILSSA? When did you start and what elements of your own artistic practice led you to create ILSSA?

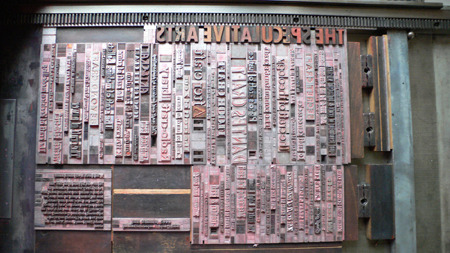

ILSSA: We were both writers who became interested in letterpress printing as a hands-on extension of writing. Writing is thinking, and making is thinking, so self-publishing always seemed like a way of thinking things through from beginning to end. Self-publishing is an empowering practice because it enables us to take the production of media into our own hands and reach out to others with messages that have not been “vetted” or approved by anyone else.

We met in New York in 2002 because we were both involved with the Brooklyn-based book artist alliance Booklyn and served on its board for many years. Eventually, we both made our ways to graduate school. Bridget went to the University of Alabama for the book arts program, and Emily went to Yale for the graphic design program. We were learning a lot in our programs, but were frustrated by how we fit into them. We wanted to learn the skills that were the focus of our programs, such as visual communication and hand binding, as tools for making works of art, but we were interested in the exploratory and investigative aspects of the making process. We wanted to make things that we didn’t know already what they were: handmade, considered, conceptual, experimental projects. We wanted to prioritize process and move the lens away from product. And then we figured: There must be others like us. We should find them.

The question became what was “like us”? We knew printing or artist publications were too limiting and wanted to learn from other people who created different types of things. So we asked ourselves, if we’re to begin with letterpress, why did we like it so much? We like the slow, meditative quality of the process, the reuse of old equipment, the hunting and gathering of such equipment over a lifetime of practice, the self-education involved in learning something uncommonly taught, its embedded skepticism of new consumer-based novelty, the fact that the time poured into it could never be adequately compensated and that compensation wasn’t the point of the activity. This is when we realized, “Aha! Obsolete technology. We should find other makers who use obsolete technology (OT).”

We were not seeking makers who chose to faithfully reproduce historic forms. We were looking for makers who sought to experiment, or who use OT for a specific, carefully considered, meaning-driven purpose. So our mission became creating a membership organization for those who make “conceptual or experimental work with obsolete technology.”

EW: What, in your opinion, is impractical labor? What are some examples of the impractical labor created with obsolete technology by your membership?

ILSSA: By “impractical labor” we mean a category of work that does not prioritize efficiency or practicality. “Impractical labor” prizes the experience of laboring. In our society the product is typically seen as a means of exchange. The word “practical” has been redefined as “marketable.” “Impractical labor” creates an opening for work that is done for reasons other than financial return. It is work that is a labor of love.

OT employed by our membership includes tintypes, ceramics, robotics, calligraphy, comic books, fibers, typewriters, deaccessioned books, analogue video, letter writing, Polaroids, vacuum tubes, printmaking, hand bookbinding, and heirloom seed saving. Our membership is self-identified: anyone is invited to join and our members are made up of a very diverse bunch of makers.

EW: On your website you refer to “Speculative Arts” as breaking down the boundaries between fine art, craft, and design. What is the history of this term and how do you see that taking place among the membership of ILSSA?

ILSSA: We came up with the name “Impractical Labor in Service of the Speculative Arts” by painstakingly trying to define our interests, and matching each related concept to its definition in the OED. We chose “Speculative Arts” as an umbrella term for experimental work that breaches the disciplinary distinctions that were frustrating us, such as art, craft, design, writing, conceptual work, and handmade work. For us “Speculative Arts” is work whose definition or destination is not predetermined. For each of our members the exact referents of “Speculative Arts” is different.

We have members like Corina Reynolds who makes performative work or Anne Percocowho makes installation-based work, but who utilize different kinds of obsolete technology depending upon the project. We have members whose whole project is oriented around an obsolete practice: ALLS, who compose beautiful and poignantly funny letters using typewriters on-demand as a social service. There is also action weaver Travis Meinolf, who weaves in public places, teaches weaving, and whose finished weavings function in the economy in a very thoughtful fashion.

EW: ILSSA appears to be an art project in itself that is a conceptual performance, an act of social practice with a particular aesthetic, and a functioning organization with a concrete purpose. How do you negotiate the different elements of the project?

ILSSA: As we were looking for other makers who shared our interest in obsolete technology most of the contemporary art we liked was interdisciplinary, post-studio, de-materialized social practice. ILSSA was, from the start, our art project. If no one was interested in it but us, that was OK, but to our pleasant surprise we now have over 150 members.

Interestingly enough, no negotiation between an art project and an organization is needed. We think of ILSSA as a morale-boosting organization. As the co-operators we try to identify what projects would most benefit our membership, and then we try to do those things.

As ILSSA has grown it has given us new ideas for projects. Some current areas of interest: How can we better connect our laborers and foster collaboration or a sense of community? What are the characteristics of meaningful, rewarding, fulfilling labor, and how can we help each member garner more satisfaction from her endeavors?

EW: What do you think have been some of the biggest accomplishments of ILSSA so far? What’s next?

ILSSA: In 2009 we came up with an idea for the Obsolete Technology Lab. We wanted to travel to different institutions, assess the discarded technology locked away in storage facilities, and set up labs for their inventive reuse. We envisioned hunting down manuals, sourcing practitioners who could teach workshops, and organizing everything into useful areas. We proposed this as a residency at the Visual Studies Workshop (VSW) in Rochester, New York. They turned down our proposal, but they really liked the idea. Then one graduate student, Dan Varenka, got really excited and went ahead and set up the lab himself!

We realized that we didn’t need to travel to create OT Labs, but people could do it for themselves. At VSW they call the OT lab “The Cage,” and the obscure video equipment there has already been utilized by students for their work. Similarly, Washington University and All Along Press (AAP) invited us out to St. Louis, and we created the “Obsolete Technology Guide for the Citizens of St. Louis.” This conception of the “OT Lab” was a focused directory of existing local resources for obsolete technology instead of a newly created facility.

We’re starting a new publishing project this fall, Standards & Practices, which provides a frame for this type of call-and-response activity. The Standard describes an action or activity, and is an open invitation for Practice. So, the first Standard was the proposal to start Obsolete Technology Labs, and the first two Practices of this Standard are the VSW Cage and the St. Louis Guide. Each Standard could have an infinite number of Practices.

In January 2012 we have our first exhibition, at St. Mary’s College in Indiana. For this exhibition all ILSSA members are invited to save a remnant of their process from each day of 2011 in which their labor is impractical. Remnants are to be placed in identified, dated envelopes, and stored in chronological order. In early January 2012, members will ship their boxes to the gallery. The culminating exhibition will display all remnants grouped together by day, uniting the labor efforts of impractical laborers wherever they may be, whatever they may be doing. After the exhibition, St. Mary’s sculpture students will use these remnants to create a new project, and envelopes will be collated, bound into books, and shipped back to each participating member. For this exhibition we’re creating a publication, inviting members to contribute essays and visual responses on specific topics.

Bridget Elmer is an artist, bookmaker and letterpress printer working in Asheville, NC, where she is rebuilding her platen press, tuning up her 1966 flatbed truck, and retrofitting open source philosophy to book technologies. Bridget received her MFA in the Book Arts from the University of Alabama in 2010, and she will graduate with her second Masters, in Library and Information Studies, in 2011. Bridget has taught at Florida State University, The Press at Colorado College, and Ox-Bow among others. She currently serves as an Instructor at Asheville BookWorks and is the Program Assistant at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center (BMCM+AC).

Emily Larned is an artist, writer, designer, educator, and letterpress printer, working in Bridgeport, CT. Her artist publications are internationally collected and exhibited and she has taught and lectured widely. She received her MFA from Yale School of Art in 2008 and is Chair and Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at Shintaro Akatsu School of Design (SASD) at the University of Bridgeport. She is currently studying handloom weaving, basket making, mandolin playing, and time.

Eleanor Whitney is a writer, musician, and educator who grew up in Maine and lives in Brooklyn, New York. She has contributed to a variety of publications and blogs about art, music, literature and culture. She received her BA from Eugene Lang College and is pursuing her Masters in Public Administration at Baruch College. She is currently the Program Officer for External Affairs and Fiscal Sponsorship at NYFA.